Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light for my path. (Psalm 119:105)

Psalm 91 (NIV)

1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty. 2 I will say of the LORD, "He is my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust."

3 Surely he will save you from the fowler's snare and from the deadly pestilence. 4 He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart. 5 You will not fear the terror of night, nor the arrow that flies by day, 6 nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness, nor the plague that destroys at midday. 7 A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you. 8 You will only observe with your eyes and see the punishment of the wicked.

9 If you make the Most High your dwelling – even the LORD, who is my refuge – 10 then no harm will befall you, no disaster will come near your tent. 11 For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways; 12 they will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone. 13 You will tread upon the lion and the cobra; you will trample the great lion and the serpent. 14 "Because he loves me," says the LORD, "I will rescue him; I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name. 15 He will call upon me, and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble, I will deliver him and honour him. 16 With long life will I satisfy him and show him my salvation."

Notes

1. Psalm 91 is a wonderful psalm of encouragement when contemplating looming difficulties as it promises protection, rescue and preservation to those who put their trust in the LORD/Yahweh (verses 1 and 9) and love him (verse 14). The psalm describes salvation from harm, protection from deadly illnesses, freedom from fear, angelic rescue when all else fails, the help of God himself whenever trouble is threatening and once the storms are over a long satisfying life with the assurance of eternal salvation.

2. Well, that is what it appears to say. However, bad things still happen to good people. Faithful believers suffer persecution and martyrdom. Christians die from natural disasters whether cancer, car accidents or mountain falls. So Psalm 91 is not true for every situation, though it seems to allow for no argument. Could this possibly be wishful thinking that is intended to comfort the easily deceived? It is not unreasonable to expect such a thought to cross our mind so it cannot be ignored. It has to be addressed.

3. Bear in mind though, that a psalm is not a theological treatise. It is not even a prose essay presenting balanced arguments about how we should approach suffering. It is a psalm. It is poetry.

4. The NIV Bible version of Psalm 91 displays the psalm in a poetic structure but that is an English language interpretation that is not very helpful. Psalms are best read in the form the author used and that is discoverable.

5. Each line of Hebrew poetry is in two or three parts with the indented second and third parts rephrasing or developing the first. Fortuitously, the English verse numbers match this aspect of the Hebrew poetic lines.

6. English poems are written to rhyme but Hebrew psalms have a theme and each line/group of lines (a strophe) is devoted to an idea about the theme. This translates well into other languages.

7. In this psalm the strophes are all couplets and the psalm is divided into two stanzas that have the same theme (dwelling in Yahweh) and matching ideas (protection, rescue and preservation) about how dwelling in Yahweh works out in the practicalities of everyday life. But, of course, that is about the life the psalmist lived so we need to understand something about that before we can relate the psalm’s teaching to our own lives.

8. Parallelism is also a key feature. This is both within each line or strophe so the idea is repeated, contrasted or developed, and between strophes so one strophe is paired with another. Further details of Hebrew poetic structure are available in Introduction to Hebrew Poetry.

9. God is addressed as ‘LORD.’ That is how God’s name, Yahweh, is expressed in most English translations, following an ancient Jewish tradition, but Yahweh is the name Moses was told to use and it is the way God is addressed in Psalm 91 and throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, the Old Testament. Yahweh will therefore be used in the rest of these notes.

10. The following layout expresses the poetic structure of Psalm 91 as it would have been understood by the psalmist and his Hebrew speaking community.

Psalm 91

Dwelling in Yahweh: The Ongoing Experience of Salvation

| Stanza 1 | The psalmist’s experience | |

| X | 1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty. 2 I will say of Yahweh, “He is my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.” | Shelter, resting in the shadow, refuge and fortress are about personal security, ‘dwelling in Yahweh,’ and it is all found in God – Yahweh, the Most High, the Almighty. |

| A | 3 Surely he will save you from the fowler’s snare and from the deadly pestilence. 4 He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart. | Protection. Yahweh can be expected to care for and protect his people from danger and threats. |

| B | 5 You will not fear the terror of night, nor the arrow that flies by day, 6 nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness, nor the plague that destroys at midday. | Rescue. There is no need to fear any danger such as the frightening terrors of the night, an enemy’s attack in the day or the most awful of devastating diseases. |

| C | 7 A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you. 8 You will only observe with your eyes and see the punishment of the wicked. | Preservation. Yahweh may appear to be singling you out for preservation as everybody else is destroyed but bear in mind that Yahweh wants to have this role with everyone. |

| Stanza 2 | Encouragement to follow the psalmist’s example | |

| X1 | 9 If you make the Most High your dwelling – even Yahweh, who is my refuge – 10 then no harm will befall you, no disaster will come near your tent. | Yahweh’s title, the Most High, is repeated as a reminder that he is the ultimate authority and power so ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ is the safest place to be. The link with refuge and fortress is in ‘no harm’ and ‘no disaster.’ |

| A1 | 11 For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways; 12 they will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone. | Protection. This may be so unexpected and dramatic that it seems that God has intervened directly. |

| B1 | 13 You will tread upon the lion and the cobra; you will trample the great lion and the serpent. 14 “Because he loves me,” says Yahweh, “I will rescue him; I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name. | Rescue. Other dangers come from the lions and snakes which were a real risk in the psalmist’s rural environment. |

| C1 | 15 He will call upon me, and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble, I will deliver him and honour him. 16 With long life will I satisfy him and show him my salvation.” | Preservation. Yahweh confirms his commitment to respond to his people, to be with them and preserve their lives. |

11. The pattern of the psalm, the parallelisms and ideas would be memory prompts and, as essential aspects of the psalm, they contribute to its meaning. We, therefore, need to take note of that structure and the world in which the psalmist lived even before we consider reading the psalm through the filters of NT insights, 2,000 years of Christian teaching and the culture and ideas of the 21st century.

12. Psalm 91 is unusual, possibly unique, as it has many figures of speech, about 50, packed into 275 words. Other psalms in comparison rarely have more than ten. One word may require a whole page of explanation to enable us to sense the psalmist’s meaning.

13. The frequency and nature of the figures of speech are perhaps key reasons why Psalm 91 does not appear to flow like other psalms. Instead, the psalmist seems to jump from one thought to another with no obvious connection.

14. In Psalm 91 some figures of speech are obvious but to understand others, ‘ordinary’ words need to be understood figuratively too, and some relate to the culture and lifestyle of the period so we need to change some of our in-built perspectives to appreciate them. Here, then, is my list of the words and phrases that are used either as figures of speech or have a significant meaning that may not be immediately apparent to a modern day reader: dwells, shelter, the Most High, rest, shadow, Almighty, Yahweh, refuge, fortress, save, the fowler’s snare, the deadly pestilence, cover you with his feathers, under his wings you will find refuge, shield, rampart, terror of night, the arrow that flies by day, pestilence, stalks in the darkness, plague, destroys at midday, a thousand, fall at your side, ten thousand, your right hand, it, observe with your eyes, dwelling, refuge, harm, befall you, disaster, tent, angels, guard you in all your ways, lift you up in their hands, strike your foot against a stone, tread, the lion, the cobra, trample, great lion, the serpent, rescue, protect, trouble, deliver, honour, long life, satisfy, salvation – 52 in all!

15. As well as the pattern and layout of the psalm we need to be aware that this is not logical prose. It is poetry that uses figures of speech, especially metaphors and hyperbole. These involve the reader’s emotions as well as their mind as they connect with their personal experiences that seem to link in with the psalmist’s world.

16. To understand these ‘word pictures’ requires knowledge about the world and culture in which the psalmist lived.[1]

17. The Bible is not concerned with providing an historical record of the details of how people lived but clues are available. From the psalmist’s description of his life it seems likely that he lived in a rural community, probably in a small village with a city not far away (there was a strong community structure in ancient Israel featuring the extended family, clan, tribe and nation). He seems to have been a self-sufficient subsistence farmer so would spend most daylight hours farming, hunting and foraging, seeking to ensure a supply of food, water, clothes etc in order to survive. It was a life of persistent insecurity, stress and danger as there was a risk from marauding armed men as well as the ‘normal’ risks from the environment such as crop failure, illness, accidents and attacks from wild animals. This has many similarities to life in the 21st century rural third world and in unstable countries but is far removed from the culture and lifestyle of Western civilisation.

18. The psalmist’s spiritual teaching about dwelling in Yahweh is based on his personal experiences throughout life that point to a vibrantly rich truth that is as relevant to us in our day as ever it was to the psalmist’s community around 2,500 years ago.

19. As always we need to be aware that though Scripture has been written for us it was not written to us. It was not even written for reading. Books/scrolls were precious and rare so everyone would need to know the psalm by heart. They were an oral society even though it is reasonable to assume that literacy was an established cultural feature. Having heard the psalm read or recited by older members of the family and community, children and young adults would quickly learn. It evidently became part of the national ‘hymnbook’ so would have been used both in national celebrations and throughout the nation at local communal worship events. It would have been a ’teaching psalm’ something like John Wesley’s hymns of the eighteenth century (see Psalm 66 note 83).

20. The first strophe in each stanza presents the theme of the Psalm, ‘dwelling in Yahweh,’ so, rather than label them A-A1, I use X-X1, as they function similarly to the ‘punchline’ strophe in the centre of a chiastic psalms (see Psalm 11 as an example). The following strophes (A-A1, B-B1, C-C1) present evidence about how ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ works out in everyday life. We therefore, need to examine these strophes, a pair at a time.

Strophes X-X1 Dwelling in Yahweh

Dwells, dwelling

X 1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will rest in the shadow of the Almighty.

2 I will say of Yahweh, "He is my refuge and my fortress,

my God, in whom I trust."

X1 9 If you make the Most High your dwelling –

even Yahweh, who is my refuge –

10 then no harm will befall you,

no disaster will come near your tent.

21. Dwells/dwelling has the same root in English but in Hebrew different words are used, though this does not appear to be significant. The way the words are translated all refer to a place for living, abiding, habitation, settling, remaining, residing and such. This is not about the nature of the premises (brick built or a grass hut, a palace or a hovel) but about its purpose. It is permanent, not temporary. It may be left for a while or neglected but is still a place to return to. Perhaps ‘home’ sums it up best. The etymology of the word is only a small aspect of its meaning.

22. More crucial is what it meant in the culture of the day. People in Scripture were strongly place-orientated as is demonstrated from the beginning of their occupation of the Land (Joshua 13-21). People were named by where they lived (eg Jesus of Nazareth, David, son of Jesse of Bethlehem). Land, homes, villages and towns were occupied by succeeding generations of the same family for many centuries. People ‘dwelt’ where they were born, lived, married and died. Their land and home was a major part of each family’s ancestral inheritance.

23. ‘Dwelling’ is more than an intellectual concept. It is about feelings and emotions but even more so, it is something that goes deep into our souls. For some it means more than life. Some people would rather die than leave their home or see it destroyed. For example, the Jews exiled in Babylon seem to have grieved more over the destruction of Jerusalem than over their failure to live up to their Covenant responsibilities (Psalm 137 especially notes 65-66).

24. The depth and breadth of this meaning underlies the concept of ‘dwelling in Yahweh.’ In strophe X the psalmist presents his own experience, his testimony, then in strophe X1 he invites us to follow his example.

25. This is the lead metaphor in both stanzas. Everything else depends on this.

26. So what does ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ mean for me, a modern reader of this psalm?

27. It is when Yahweh means more to me than life itself. My standing in Yahweh is my true identity – my identity is not about my profession, my status in society, my role in church life or family affairs. It is all about what Yahweh means to me and what he wants of me.

28. Yahweh is the one I come back to from the busyness of the day for rest and reflection, to rebuild my resources.

29. Yahweh is the one I turn to for inspiration and guidance about every affair of life.

30. Yahweh is the one I turn to in times of distress and turmoil.

31. ‘I am a believer so all the promises in this psalm must relate to me,’ might be said, but no, that is not necessarily true! Replace, ‘I am a believer’ with any one of, ‘I am a Christian, I go to church, I pray, I would never hurt anyone, I try to live to please God.’ None are necessarily true for their focus is on ‘me’ and not on Yahweh.

32. This metaphor is a reminder that if I am to ‘dwell in Yahweh’ and experience Yahweh’s protection, rescue and preservation throughout the troubles of life I must put him first in every aspect of my life. God is not my servant to come at my call and to be ignored at other times. He is my God for me to worship and serve with everything I have. It is about having a living and vibrant faith and an all-consuming commitment to living for our God and Saviour above everything else. This idea is echoed in the New Testament in phrases such as:

Jesus replied: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind’ (Matthew 22:37).

Therefore, I urge you, brothers, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God – this is your spiritual act of worship. Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is – his good, pleasing and perfect will (Romans 12:1-2).

For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain (Philippians 1:21).

33. The concept of ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ is also expressed in NT as being ‘in Christ’:

You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise (Galatians 3:26-29).

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near through the blood of Christ (Ephesians 2:13).

Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, since as members of one body you were called to peace. And be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly (Colossians 3:15-16).

It is because of him [God] that you are in Christ Jesus, who has become for us wisdom from God – that is, our righteousness, holiness and redemption (1 Corinthians 1:30).

34. Strophes X-X1 expand on this understanding about Yahweh before they explore how it was reflected in the practical realities of life.

The name and titles of God

X 1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will rest in the shadow of the Almighty.

2 I will say of Yahweh, "He is my refuge and my fortress,

my God, in whom I trust."

X1 9 If you make the Most High your dwelling –

even Yahweh, who is my refuge –

10 then no harm will befall you,

no disaster will come near your tent.

35. We do not think readily of the titles of God as metaphors but as ‘word pictures‘ that is what they are.

36. God’s name and titles reflect aspects of his character and nature. Throughout Scripture they are not allocated randomly. They are there for a purpose that reflects what the author of the passage concerned thought was appropriate and equally how God chose to reveal himself.

37. The name and titles used are all in strophe X though the Most High and Yahweh are repeated in strophe X1 and Yahweh again in strophe B1.

38. Yahweh is not a title of God but his name, that is used 7,000 times in Scripture. It reflects the concept that God is the ‘Always I Am’ who wants a relationship with the people he created.

39. The Most High (Elyon) is used 45 times as a title of Yahweh with reference to his supremacy in status and power. For example:

Let them know that you, whose name is Yahweh – that you alone are the Most High over all the earth (Psalm 83:18).

You said in your heart, “I will ascend to heaven; I will raise my throne above the stars of God; I will sit enthroned on the mount of assembly, on the utmost heights of the sacred mountain. I will ascend above the tops of the clouds; I will make myself like the Most High” (Isaiah 14:13-14).

The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you (Luke 1:35).

40. ‘Dwelling’ in Yahweh is related to ‘the Most High’ in both strophe X and strophe X1 thus emphasizing the link. Surely, there cannot be a better place to dwell!

41. The Almighty (Sadday) is used 48 times and suggests overwhelming power and authority so it closely parallels the meaning of ‘the Most High.’

42. When the generic ‘god’ (el) is used to refer to the one and only true God, it takes a capital G – ‘God.’ An extra descriptive word or phrase is sometimes used to make clear that Scripture is referring to God, ‘my God,’ ‘Almighty God’ etc.

43. This psalm is not primarily about all the good things Yahweh does for his people. Rather it is about Yahweh himself. And Yahweh, the Most High God, the Almighty invites his people to ‘dwell’ with him. That is stunning. And very different to the relationship any other god has with their followers.

44. Other gods are distant from their worshippers. They are arbitrary and contrary. Gods made in the image of human beings. What a contrast!

Shelter and shadow, refuge and fortress, harm and disaster

X 1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will rest in the shadow of the Almighty.

2 I will say of Yahweh, "He is my refuge and my fortress,

my God, in whom I trust."

X1 9 If you make the Most High your dwelling –

even Yahweh, who is my refuge –

10 then no harm will befall you,

no disaster will come near your tent.

45. ‘Shelter’ is the choice of most modern translations compared to the ‘secret place’ of KJV, nevertheless, the idea of hiding can be an aspect of its meaning. It is coupled with shadow in the second half of the line so the metaphorical imagery is related.

46. Being in the ‘shadow’ of someone is, to me, a negative image about being restricted in development or opportunity because of being close to a more powerful and more obviously gifted person who takes centre stage. I am sure that is not what it means so I have had to work hard to put that understanding out of mind. I need to tune in to what was in the author’s mind when he wrote these words and try to imagine what his first readers would ‘see’ in that phrase.

47. Interestingly Hebrew uses two words for shadow. On 27 occasions, like here, the Hebrew word relates to shadow providing shade and protection. A different word is used on 18 occasions when shadow relates to darkness and gloominess (eg. the shadow of death).

48. I was studying Psalm 91 in 2020 during the Covid lockdown and was very frustrated as I could not see how the apparently disparate statements in the psalm were interrelated. Coincidentally, we had almost wall to wall sunshine for two months so I took the opportunity to regrout the patio. I was crawling around the patio working hard in blazing heat and when I needed a rest I automatically looked for a shady spot. I realised one day that I never really think about what provides the shade. I take it for granted. That helped my reflections on Psalm 91 as it occurred to me that the psalmist might have been in a similar situation. Then the penny dropped – all these random disparate statements in Psalm 91 were actually features of the psalmist’s day to day life!

49. Ancient Israel was a rural community, towns were small and townspeople would still keep a few sheep or goats on the premises and have their own plot of land to grow crops. In such communities more than 80% of time and energy would be spent, almost always out of doors, on ‘survival’ activities to ensure there were enough crops to provide food, clothing and other essentials throughout the year and perhaps a little to spare to set aside for the bad times and an occasional celebration.[2]

50. In that context I imagine the psalmist out and about in the busyness of his life in the blazing heat of the Middle East. He stops for a rest, a few moments to reflect on what he has achieved or to plan his next activity or maybe have a conversation with a passing neighbour. And what does he do? He looks for shade, somewhere to stand or sit to provide a brief respite from the heat of the sun. He heads for a nearby tree, or perhaps he has already prepared a bower of branches ready for such a moment. So he ‘rests in the shadow.’ In my clumsy, functional, ‘educated’ way I think of ’shade’ as I read ‘shadow.’ But that is inadequate. ‘Shade’ relates to what I want/need while ‘shadow’ refers to the provision of the shade.

51. Shadow is paralleled by shelter so, if shadow is a metaphor based on shielding from the sun, shelter is likely based on the need for protection from adverse weather such as rain, cold or wind.

52. So these metaphors point to Yahweh – for the psalmist as well as us. When needing temporary relief the psalmist turned to Yahweh – and so must I. Referring to Yahweh as ‘Almighty’ says it all. He is the all-sufficient one – for the minor stresses of life as well as for the big issues. I must focus on the Almighty – not on his blessings.

53. I reflect, that in conversation, thought and prayer, I refer to God as God more often than not. I need to take a lesson from the psalmist’s example and use alternative terms that express something of God’s character and person that is relevant to the context.

54. So exploring the metaphor, connecting it with the actual situation it mirrors, and relating that to my life situation assists in a richer understanding of the phrase the psalmist uses.

55. In the psalmist’s life providing shelter or shadow would have been only an occasional need but the psalmist still relates it to Almighty God. I tend to reserve referring to God as Almighty for the big issues in life. It seems I need to change my attitude.

56. The psalmist then develops the analogy as he refers to Yahweh as my refuge and my fortress (strophe X) and parallels that with no harm and no disaster (strophe X1).

57. Refuge is used 93 times in OT but not at all in NT and most references are about Yahweh as a refuge.

58. Of the 44 times in Psalms that refuge is used, all but two are about Yahweh and on 15 occasions a second metaphorical word is also used. These are rock x6, shield x3, fortress x2, shadow x2, shelter x1 and wings x1. For example, here is the other reference that refers to fortress:

… be my rock of refuge, a strong fortress to save me. Since you are my rock and my fortress, for the sake of your name lead and guide me (Psalm 31:2-3).

59. Refuge refers to safety from danger and the link to fortress and the context emphasises that this danger comes from violent opposition.

60. In ancient Israel ‘city’ and fortress were virtually synonymous.[3] This is quite different to the UK and European style of ‘fortress.’ Here, a fortress is a castle for the protection of a nobleman, his family and soldiers – a limited number of people. The ordinary people would live outside the castle/fortress with little protection from aggressors. However, in Scripture a fortress is for all, not just a select few.[4]

61. The refuge seeker is looking to escape from danger so that suggests a sense of weakness whereas once in a fortress the occupier has a place of strength that is controlled and reserved and is being built up in preparation to repel assault or even to venture out in attack.

62. It is then paralleled in strophe A1 by the phrases, ‘no harm will befall you’ and ‘no disaster will come near.’ This is not a simple repetition but a development of the idea promoted in the strophe, that emphasises that dwelling in Yahweh results in freedom from harm and disaster.

63. I have known believers become intensely angry or distressed when reading strophe X1 as they contrast what it says with their own experience of suffering when Yahweh appeared to be distant and uncaring; but Scripture needs to be read in context. Psalms are poetry and use figures of speech that come without explanation as that is an aspect of how they work. And this is hyperbole. It is intended to create tension within the reader for its proposition is patently untrue in factual terms. It is a deliberate exaggeration to make a point. It builds on the premises that Yahweh is ever-present, all-powerful and is totally committed to his people. He therefore can be trusted wholeheartedly. And if anything does go wrong where is Yahweh? He is there with his people in their suffering as Hebrews 13:6 reassures us:

God has said,

“Never will I leave you;

never will I forsake you.” (quoting Deuteronomy 31:6)

So we say with confidence,

“Yahweh is my helper; I will not be afraid.

What can man do to me?” (quoting Psalm 118:6)

64. Psalm 66 (note 27) and Psalm 58 (note 16) use hyperbole but they are easier to accept as they do not challenge strongly held perceptions of personal suffering.

65. Scripture calls us to trust Yahweh even when all the ‘evidence’ we recognise calls that trust into question. This trust is modelled for us by Shadrach and his friends (Daniel 2:16-18) and even more stunningly by the author of Psalm 13 (notes 39-44) as they, wisely, took account of the ‘evidence’ of Yahweh’s promise and his track record and did not reflect only on the suffering and danger they were facing.

Trust, tent

X 1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High

will rest in the shadow of the Almighty.

2 I will say of Yahweh, "He is my refuge and my fortress,

my God, in whom I trust."

X1 9 If you make the Most High your dwelling –

even Yahweh, who is my refuge –

10 then no harm will befall you,

no disaster will come near your tent.

66. Curiously, Strophe X1 ends with two words, ‘your tent,’ that seem to contradict the image that has been created of security in a fortress refuge, sheltered by the Most High God. How can a ’tent’ be considered secure? A tent was a portable, mobile home occupied by the patriarchs in Genesis, the nation of Israel in their wilderness wanderings and by campaigning armies in the times of the monarchy. It no longer had a place in the normal affairs of life once the nation had settled into its cities and villages and were absorbed in an agrarian culture. Those experiences of their ancestors were not forgotten, however, as living in temporary shelter was a feature of the annual Festival of Sukkot (alternatively referred to as the Feast of Tabernacles, Booths or Shelter) when everyone lived for a week in a temporary shelter of branches.

‘So beginning with the fifteenth day of the seventh month, after you have gathered the crops of the land, celebrate the festival to Yahweh for seven days; the first day is a day of rest, and the eighth day also is a day of rest. On the first day you are to take choice fruit from the trees, and palm fronds, leafy branches and poplars, and rejoice before Yahweh your God for seven days. Celebrate this as a festival to Yahweh for seven days each year. This is to be a lasting ordinance for the generations to come; celebrate it in the seventh month. Live in booths for seven days: All native-born Israelites are to live in booths so your descendants will know that I had the Israelites live in booths when I brought them out of Egypt. I am Yahweh your God’ (Leviticus 23:39-43).

67. Booths were not tents but the point is that the role of using temporary living accommodation remained a feature of national life.

68. KJV translates ‘tent’ as ‘dwelling’ and some modern translations refer to home, door or omit it, as if it is of no consequence.

69. Mounce[5] says that here and in three other references (Psalm 78:51, 132:3 and Lamentations 2:4) it refers to ‘a common house.’ Maybe so, but also we should consider the possibility that tent could be a poetical reference to a home but emphasising its temporary nature.

70. My impression from studying the Psalms is that psalmists choose their words carefully and may pack a lot of meaning into few words – which is a feature of all poetry.

71. Tent is used for a reason and it seems most likely that the temporary nature of such a home is the relevant feature of interest.

72. I think the psalmist is making the point that though we may and should live our lives ‘dwelling in the Most High,’ paradoxically, we still live out our lives with the normal uncertainties of human existence with no guarantees of the future. It is as if we still live in tents!

73. The psalmist expresses poetically and in a pre-Christian understanding the idea of living by faith and trust that Paul expounds in the NT in such texts as:

Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen. For what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal (2 Corinthians 4:16-18).

You, however, did not come to know Christ that way. Surely you heard of him and were taught in him in accordance with the truth that is in Jesus. You were taught, with regard to your former way of life, to put off your old self, which is being corrupted by its deceitful desires; to be made new in the attitude of your minds; and to put on the new self, created to be like God in true righteousness and holiness (Ephesians 4:20-24).

74. Having developed this understanding of the meaning of tent it may be significant that strophe A ends with trust – and that is the final word in the original Hebrew as well as in the English translation. This could be another example of the parallelism that is such a major feature of biblical poetry. The security that is obtained when we build a life based on Yahweh (trust) is compared with the ephemerality of life based on our own resources (tent).

75. The major emphasis in strophes X-X1 is about dwelling in Yahweh and that brings protection from the ‘ordinary’ stresses of life (shelter and shadow) as well as the unexpected and potentially life-threatening dangers from aggressors (refuge and fortress).

76. Strophes X-X1 introduce the theme of the Psalm while the following strophes A-A1, B-B1 and C-C1 present evidence about the benefits of ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ in ideas about Protection, Rescue and Preservation that back his claim.

Strophes A-A1 Protection

Fowler’s snare and deadly pestilence

A 3 Surely he will save you from the fowler's snare

and from the deadly pestilence.

4 He will cover you with his feathers,

and under his wings you will find refuge;

his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

A1 11 For he will command his angels concerning you

to guard you in all your ways;

12 they will lift you up in their hands,

so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.

77. The ‘fowlers snare’ was a feature of life throughout the ancient Middle East and appears in Egyptian and Assyrian wall paintings. There has always been profuse birdlife in Israel and as the country lies on a main migratory route between Africa and Europe and West Asia[6] catching birds for food (that is what a fowler does) would be a seasonal occupation. Such a migration could have been the background for the miraculous supply of quail[7] to the Israelites in the desert (Numbers 11). Snares[8] would be left out where birds where known to land while the fowler would hide nearby ready to claim his trophies and quickly reset his snares.

78. There are only two other references to a fowler in Scripture (Psalm 124:7, Proverbs 6:5) and all use the same analogy of escaping from a snare. Apart from this imagery the use of this metaphor illustrates something deeply significant about the psalmist’s mindset and attitude. To a fowler a bird meant a family meal, hunger satisfied, perhaps even one more tiny step in preventing starvation that was a perennial fear, so if a bird escaped, we might expect him to express disappointment and irritation. But that is not on the psalmist’s mind in this metaphor. Instead, he is thinking of the bird and its escape from a trap.

79. That provides a fascinating insight into the mind and emotions of an Israelite living upward of 3,000 years ago in the Middle East. In the midst of the grind of life he pauses to reflect on the imagery of a bird escaping from his snare. A potential meal lost is a bird freed to live on. Here is an expression of beauty, compassion and wonder even while primarily interested in providing the basic needs of life.

80. This contrasts with the commonly perceived understanding of human needs that, until the basic needs of life, such as food, shelter and clothing, are met, there is no interest or time to consider the more aesthetic aspects of life. This concept is often expressed by reference to Maslow’s hierarchy of need[9] as illustrated in the diagram.

81. The fowler’s snare is paired with a deadly pestilence and that describes an illness that would have affected many people in a community. Some would have died, often very quickly, but then the illness would disappear and may not return for years. This likely refers to an epidemic infectious disease such as what we now know as measles, cholera or polio. Both images refer to protection from the prospect of sudden and unexpected death.

Feathers and wings, shield and rampart

A 3 Surely he will save you from the fowler's snare

and from the deadly pestilence.

4 He will cover you with his feathers,

and under his wings you will find refuge;

his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

A1 11 For he will command his angels concerning you

to guard you in all your ways;

12 they will lift you up in their hands,

so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.

82. The second line of Strophe A describes a young bird that is protected by a parent bird who, in the face of danger gathers the chick and hides it with his feathers/under his wings.

83. Cover with feathers naturally parallels finding refuge under wings but the line has three parts with the third part, oddly, being about a shield and rampart.

84. This is the only reference to being covered/protected with feathers but being sheltered by wings is quite common, for example:

May you be richly rewarded by Yahweh, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come to take refuge“ (Ruth 2:12).

Keep me as the apple of your eye; hide me in the shadow of your wings from the wicked who assail me, from my mortal enemies who surround me (Psalm 17:8).

Both high and low among men find refuge in the shadow of your wings (Psalm 36:7).

I will take refuge in the shadow of your wings until the disaster has passed (Psalm 57:1).

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing (Matthew 23:37-38, Luke 13:34-35).

85. The singular is used both here and throughout Psalm 91 but Jesus uses the plural. Both are appropriate on each occasion so there is nothing significant about this difference.

86. The imagery of a parent bird providing safety for its young usually uses the female gender as Jesus did (Matthew 23:37) but Psalm 91 uses the masculine gender following an ancient linguistic custom as the emphasis is not on the role but on Yahweh, the provider.

87. The imagery of deadly pestilence parallels the fowler and the parent bird imagery. They are linked by the idea of protection from harm.

88. The idea of protection is continued in the third part of line two as shield (sinna) refers to a large shield that protected the body from head to toe and rampart (it is used only this once in Scripture) refers to the battlements on top of the city wall that protects defenders (and see note 60). The parallels appear to be at odds but the idea promoted in strophes A-A1 is about protection and that is the link. The images used are based on ordinary features of the psalmist’s life. The mixing of metaphors is a strong hint that the psalmist does not want readers to take his words literally. They are all figures of speech based on his ordinary life experiences that are used to aid understanding of Yahweh’s role in our lives.

89. He clarifies this point in his declaration that they are demonstrations of Yahweh’s faithfulness, and a reason for dwelling in Yahweh.

Angels, guard, lift you up in their hands, not strike your foot against a stone

A 3 Surely he will save you from the fowler's snare

and from the deadly pestilence.

4 He will cover you with his feathers,

and under his wings you will find refuge;

his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

A1 11 For he will command his angels concerning you

to guard you in all your ways;

12 they will lift you up in their hands,

so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.

90. Whereas strophe A uses a number of images about being protected from external threats such as sudden attacks, advancing armies and natural disasters the parallel in strophe A1 mentions only one threat and this is an accidental fall. ‘Guarding’ will be provided, not in prevention but in the mishap itself there will be a miraculous angelic intervention to protect from injury.

91. Our cynical side protests: This image is over the top and unrealistic. If anyone really believes these promises they will be horribly disappointed. The world does not work like this. God does not work like this! Really? What then about,

‘Now to him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to his power that is at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, for ever and ever! (Ephesians 3:20-21)?

We generally accept this but when practical details of how this could work out in practice as in Psalm 91 we baulk. This is, of course, another example of hyperbole making the point again that Yahweh can be trusted whatever contradictory evidence is seen.

92. To understand this Scripture we need to consider what the psalmist might have had in mind. I wonder if he refers to the times when he left home on a few days hunting trip or even on a selling/shopping visit to the city market. Travelling across the open countryside was fraught with danger especially when travelling quickly and quietly when on a hunting or foraging trip or when returning laden with the spoils either from the hunt or the market. A simple trip in a lonely place could have devastating consequences. The psalmist recognised that a safe arrival was not only due to his strength, balance and agility. There were occasions when he sensed it was because of a direct intervention of God’s spiritual forces.

93. A casual reading of this strophe, that takes it out of context, may suggest the Bible is teaching about ‘guardian angels’[10] that may be referred to in Hebrews 1:14:

Are not all angels ministering spirits sent to serve those who will inherit salvation?

94. The idea of guardian angels is actually not as clear cut as we might suppose even though the role of angels providing personal protection is not uncommon in the Old Testament, though it is only ever in the singular. Sometimes it seems to refer to God himself. Here are some of the relevant texts:

… Yahweh, before whom I have walked, will send his angel with you and make your journey a success, so that you can get a wife for my son from my own clan and from my father’s family (Genesis 24:40).

“May the God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked, the God who has been my shepherd all my life to this day, the Angel who has delivered me from all harm – may he bless these boys (Genesis 48:15-16).

Then the angel of God, who had been traveling in front of Israel’s army, withdrew and went behind them. The pillar of cloud also moved from in front and stood behind them (Exodus 14:19-20).

I am sending an angel ahead of you to guard you along the way and to bring you to the place I have prepared (Exodus 23:20-21).

The angel of Yahweh encamps around those who fear him, and he delivers them (Psalm 34:7).

In all their distress he too was distressed, and the angel of his presence saved them (Isaiah 63:9).

Then Nebuchadnezzar said, “Praise be to the God of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, who has sent his angel and rescued his servants! (Daniel 3:28).

Daniel answered, “O king, live forever! My God sent his angel, and he shut the mouths of the lions (Daniel 6:21-22).

95. We need to be careful here. Though it sounds nice to have ‘guardian angels’ this is not a significant feature of biblical revelation. Angels are ‘messengers’ and exist to serve God. Part of that responsibility is to care for God’s people but that is a general observation, there is no specific role with individual believers. After all, God himself has promised to be with us. He will protect us. He goes ahead leading us and is behind guarding us. If we have God with us why do we need angels? The New Testament goes further for God is within us (I do not think this is mentioned in the Old Testament):

You, however, are controlled not by the sinful nature but by the Spirit, if the Spirit of God lives in you. And if anyone does not have the Spirit of Christ, he does not belong to Christ. But if Christ is in you, your body is dead because of sin, yet your spirit is alive because of righteousness. And if the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead is living in you, he who raised Christ from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit, who lives in you (Romans 8:9-11).

Don’t you know that you yourselves are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit lives in you? (1 Corinthians 3:16-17).

I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me (Galatians 2:20).

‘God has chosen to make known among the Gentiles the glorious riches of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory’ (Colossians 1:27).

Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you – guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us (2 Timothy 1:14).

Those who obey his commands live in him, and he in them. And this is how we know that he lives in us: We know it by the Spirit he gave us (1 John 3:24).

No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us (1 John 4:12).

If anyone acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God, God lives in him and he in God (1 John 4:15).

God is love. Whoever lives in love lives in God, and God in him (1 John 4:16).

96. We must also consider Satan’s use of this text to test Jesus (Matthew 4:6, Luke 4:10-11) for that is a good illustration of how not to use Scripture. Jesus reminded Satan, ‘Do not put the Lord your God to the test,’ thus emphasising we cannot get ourselves in a pickle and then expect God to bail us out. It comes back to ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ as the only safe place to be. If we are where Yahweh wants us to be and we are confident of that, we will still take sensible precautions to stay safe (for that is also a way Yahweh expresses his guidance). Yahweh himself chooses when to step in, but whether through circumstances or miraculously is his choice. And we still have no ‘guarantee’ as God has bigger and better plans than ours:

“My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,” declares Yahweh. “As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8-9).

The crunch test is: are we willing to trust him to the ultimate, as Shadrach and friends did (Daniel 3:16-18)? And see also Psalm 13 (note 39-44). We can never assume that our plans and ideas inevitably coincide with God’s will.

97. There are no close parallels between Strophes A and A1 but in Hebrew poetry there does not need to be for it is the idea expressed that provides the parallel. In both strophes the idea of protection from harm is clearly evident.

98. Strophe A is introduced with the word ‘surely’ that implies certainty and confidence as if the protection described is guaranteed but this is, of course, another example of hyperbole. The comment in note 63 applies here too.

Strophes B-B1 Rescue

Terror, arrow, pestilence, plague, lion, cobra, great lion, serpent

B 5 You will not fear the terror of night,

nor the arrow that flies by day,

6 nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness,

nor the plague that destroys at midday.

B1 13 You will tread upon the lion and the cobra;

you will trample the great lion and the serpent.

14 "Because he loves me," says Yahweh, "I will rescue him;

I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name.

99. After dark the only light would be a feeble oil lamp that was little brighter than a candle and it would be used cautiously because of the risk of fire. The terror of night and the pestilence that stalks in the darkness were therefore, frightening realities, an every-night danger.

100. Terror of night refers to something frightening as it might mean the onset of an overwhelming catastrophe, possibly of unknown cause as it is in the darkness of night while an arrow in the day refers to a danger to life that can equally arrive unexpectedly.

101. Night and day are paralleled in the second line by ‘darkness’ and ‘midday’ in relation to pestilence which is used to refer to what we would call an epidemic of a life threatening infection. Plague is an alternative word for pestilence and does not necessarily refer to the modern designation of bubonic plague.

102. These are very likely to be actual dangers that the psalmist had experienced but it is poetry so is intended to stimulate our imagination so they can be taken as metaphors for any sort of danger, whether physical, emotional or spiritual, that is characterised by fear, widespread death and serious incapacity for the idea underlying these aspects of the psalmist’s life is about rescue from danger.

103. There is only one comparable line in strophe B1 where the danger relates to a lion and cobra/great lion and a serpent.

104. Such creatures were a serious threat when out in the countryside farming, hunting or foraging. We might assume they represent dangerous opposition that openly attack or scheme secretively. That is a fair implication when we consider how the psalm relates to our own situation but in the context of both the psalmist’s lifestyle and the psalm’s poetic structure it seems most likely that the psalmist refers to danger from real predatory creatures that are known to have existed in his era.[11]

105. Lion occurs 130 times in OT translating 9 different Hebrew words. That suggests lions were common and well known in OT times though none have been recorded since 13th century.[12] ‘Great lion’ translates a different word that is used 30 times and is alternatively translated as ‘young lion’ or ‘strong lion’ so seems to refer to a more aggressive and fearsome lion.

106. The cobra (used 6 times) is a poisonous snake that lived in holes in the ground and could swallow small mammals whole.[13] ‘Serpent’ is used 15 times. It can refer to a sea monster, mythological figure as well as a snake so like ‘great lion’ it seems to refer to a more aggressive and fearsome but similar threat.

107. Both animals represent sudden, unexpected, life threatening danger. Such creatures really would pose significant dangers when travelling about the countryside. The people lived a subsistent existence, living hand to mouth with hopefully something to spare to build stores that would see them through the annual cycle of scarcity and plenty and even help them survive from starvation during the occasional prolonged drought (1 Kings 17:7, Jeremiah 17:8, Joel 1:10-12, 17-20). They mainly lived off cultivated crops and a few sheep or goats supplemented by what they obtained by hunting and foraging. Travelling alone through the open countryside or with only a few companions would therefore be a regular occurrence so the danger from wild animals represented by the lion and cobra was a very real risk.

108. And notice the promise is to ‘tread’ and ‘trample’ these creatures. Now that is over the top! It is madness! But that exaggeration is part of the poetic structure. It is hyperbole, a figure of speech that uses exaggeration to illustrate and highlight. It is startling, attention grabbing and introduces a hint of humour. An ant or cockroach will unthinkingly be despatched in this way but a lion or snake? But what about when Yahweh, the Most High, the Almighty is involved? That is the point! It changes the balance completely. It is a challenge to our faith. There is a danger we create God in our own image, thus limiting his power so he is no longer ALL-mighty. The psalmist’s theme is ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ so he is not thinking of his own puny strength but imagines how different it is when Yahweh is in control. Here is a beautiful poetic blending of the realities of life, figures of speech and spiritual lessons that speak into our minds, emotions and spirits. It is stunning poetry of the highest class and rich in spiritual truths.

109. The second line of strophe B1 is part of Yahweh’s speech (verses 14-16) so it is understandable that English translations include it in their final stanza as grammatically that is where it fits. However, in the Hebraic poetic structure it is part of strophe B1. It would therefore be expected to parallel the night/darkness and day/midday of strophe B but instead it breaks the pattern.

110. The rest of the psalm fits neatly into a pattern and alternative patterns do not work so we need to work on the assumption that this is the author’s intention. Such a break in the pattern does happen occasionally – for examples see Psalm 88 (note 16) and Psalm 147 (notes 37-38). It is not a mistake but a deliberate technique that I think is designed to take attention away from the psalmist’s poetic skills and even their own experiences of Yahweh’s care to focus on Yahweh himself, to ‘love’ him and ‘acknowledge’ him as the priority in life.

Strophes C-C1 Preservation

Thousand, it, will only observe, punishment, long life, salvation

C 7 A thousand may fall at your side,

ten thousand at your right hand,

but it will not come near you.

8 You will only observe with your eyes

and see the punishment of the wicked.

C1 15 He will call upon me, and I will answer him;

I will be with him in trouble,

I will deliver him and honour him.

16 With long life will I satisfy him

and show him my salvation.

111. The metaphors in Strophe C-C1 seem to be long term in nature so I am using ‘preservation’ to express the idea featured.

112. ‘Thousand’ is used 337 times in OT and refers to a large number of people so that gives the impression of being a rounded number that is not intended to be taken as an exact figure.

Five of you will chase a hundred, and a hundred of you will chase ten thousand, and your enemies will fall by the sword before you (Leviticus 26:8).

Send into battle a thousand men from each of the tribes of Israel (Numbers 31:4).

… he is the faithful God, keeping his covenant of love to a thousand generations of those who love him and keep his commands (Deuteronomy 7:9).

David captured a thousand of his chariots, seven thousand charioteers and twenty thousand foot soldiers (2 Samuel 8:4).

My lover is radiant and ruddy, outstanding among ten thousand (Song of Songs 5:10).

Even though you have ten thousand guardians in Christ, you do not have many fathers, for in Christ Jesus I became your father through the gospel (1 Corinthians 4:15).

113. The use of ‘at your side’ and ‘at your right hand’ suggests both ‘a thousand’ and ‘ten thousand’ are being used in a similar context. The image created in our mind is of a large and an even larger army arraigned in battle order and in the destruction of a murderous battle all but one soldier is killed or is so badly injured they can no longer fight. But in this image these are not fallen enemy but companions and fellow soldiers who are put out of action!

114. That interpretation seems right but it is untrue to Yahweh’s character so cannot be the psalmist’s intention. I think it is one of those, ‘it is as if’ moments. The psalm is set in the singular. It is about the relationship between Yahweh and me (not ‘us’ – that is covered in other Scriptures). So, it is as if Yahweh is addressing me personally. However, Yahweh is Yahweh so he is addressing you too; in fact, he is addressing all of Yahweh’s followers who ‘dwell’ in him. For, being Yahweh, he can have that same intimate and devoted relationship with each of us, all at the same time. Anything less is an aspect of creating God in our own image as such a relationship is impossible anywhere else. We know in our hearts this is true but we need repeated reminders as it is all too easy to be distracted by other voices that build on our own frail nature.

115. There is no ‘it’ for ‘it will not come near you’ to relate to. It could be any one of the descriptions of catastrophe mentioned in the psalm but using ‘it’ perhaps suggests the psalmist has in view all of them as if they are representative examples of any one or other of the huge variety of crises that can destroy or damage an individual, a community, culture or land; or perhaps the evil spirit that may lie behind one or other of those crises.

116. Even though catastrophes are happening all around, the Yahweh dweller ‘will only observe.’ That phrase, especially the word ’only,’ conjures in me a sense of peace amidst turmoil, comfort in the throes of distress, rest on the battlefield. Those who dwell in Yahweh will not be involved, even emotionally. That image reminds me of:

And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus (Philippians 4:7).

… ‘this is what Yahweh says – he who created you, O Jacob, he who formed you, O Israel: “Fear not, for I have redeemed you; I have summoned you by name; you are mine. When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you. When you walk through the fire, you will not be burned; the flames will not set you ablaze. For I am Yahweh, your God, the Holy One of Israel, your Saviour (Isaiah 43:1-3).

“I have told you these things, so that in me you may have peace. In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world” (John 16:33).

… ‘we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us. We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed (2 Corinthians 4:7-9).

117. And what will the righteous see? ‘The punishment of the wicked’ – Yahweh acting in justice. There are two sides to Yahweh’s justice: standing for the righteous and punishing the wicked.

118. But who are the wicked? Contextually it is the companions, standing at his side!

119. The construction of the text certainly looks as if this is correct. However, if ‘it’ refers to any or all of the catastrophes mentioned or even the evil behind those catastrophes, this too could have a more general connection. It is the last line of the stanza, so poetically it could be linking back to the whole of the stanza and the variety of evil attacks, and appalling injuries that threaten the godly person. I see this phrase therefore, as a general statement of Yahweh’s purposes: the corollary of the blessings of dwelling in Yahweh is that those who oppose Yahweh’s call and commitment will suffer the consequences (Exodus 34:6-7). How, when and the details of that punishment are not mentioned and there is no grounds for speculation for this is not a theological treatise. It is poetry with a focus on dwelling in Yahweh and nothing else.

120. I think, therefore, that the ‘wicked’ of line 2 are the wicked who deserve God’s punishment and are not the fallen companions of line 1.

121. In strophe C1 long life contrasts with the dismissive you will only observe with your eyes in strophe C and salvation contrasts with the punishment of the wicked. That then, is another reason for the psalmist’s sense of reality to be questioned. So, once again we need to refer back to note 63.

122. Long life was a consistent feature of God’s blessing in the Old Testament and what better illustration of preservation can there be than that? It is mentioned 11 times. For example,

These are the commands, decrees and laws Yahweh your God directed me to teach you to observe in the land that you are crossing the Jordan to possess, so that you, your children and their children after them may fear Yahweh your God as long as you live by keeping all his decrees and commands that I give you, and so that you may enjoy long life. (Deuteronomy 6:1-3)

So God said to him, “Since you have asked for this and not for long life or wealth for yourself, nor have asked for the death of your enemies but for discernment in administering justice, I will do what you have asked … and I will give you a long life (1 Kings 3:11-12, 14).

Long life is in her [wisdom’s] right hand; in her left hand are riches and honour (Proverbs 3:12).

123. And salvation does not have the overtones of theological interpretation that we may ascribe through the filter of NT and 2,000 years of Christian teaching. ‘Salvation’ is used 80 times in the OT, mainly in Psalms and Isaiah, with the concept of rescue and deliverance. Only the context helps understanding of each occasion to decide if it refers to rescue from an enemy or natural disaster or perhaps conversion, heaven or a spiritual experience. Very often the focus is entirely on Yahweh and not on the act of salvation. In strophe C1 ‘salvation’ parallels ‘long life’ so the primary meaning is about rescue from the variety of potentially lethal catastrophes described. That brings the psalmist to a period of peace and comfort in his latter years. Interpreting it as a reference to eternal salvation is a Christian interpretive overlay and is unlikely to be the psalmists intended meaning.

124. Strophe C1 draws the psalm to its conclusion as it continues to address the idea of preservation. Its message is a summary of the psalm confirming that God responds to the call of his people in three ways:

‘I will be with him in trouble,

I will deliver him

and honour him.’

Deliverance, whether in the form of Protection, Rescue or Preservation, is a promise but we rarely know when or how it will come and Yahweh may have different plans to what we imagine are needed.

125. The big questions are:

Do we trust Yahweh’s word, even if there is no sign as yet of delivernce?

Are we willing to put our precious, Yahweh-blessed plans afresh on the altar?

Honour, respect, appreciation and thanks may come – or they may not – when we expect them or think we deserve them. Do we demand our rights; or are we willing to endure even more and be content with, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant,’ (Matthew 25:21)?

Concluding reflection

126. Psalm 91 is written by someone who has experienced the reality of ‘dwelling in Yahweh.’ He looks back over his life and has written this psalm to testify to his own experience (strophe X) then repeats the same points with different examples to encourage us to follow his example (strophe X1). Much of his teaching is in the form of figures of speech, especially metaphors and hyperbole that relate to what was the normal lifestyle of his era and culture. The point is that these were metaphors for the psalmist himself so it is more than us reading the text as metaphors that relate to our own lives.

127. Metaphors are significant features of Hebrew poetry. There may be up to ten in a typical psalm. Psalm 91, however, has more than fifty. At first, when reading through the filters of our Western civilisation they appear to be random disconnected statements but in fact, they relate to features of the psalmist’s everyday life and experience that are expressed poetically and not factually.

128. It takes time, requires some research and a change of perspective to understand these metaphors but they would not have needed any explanation to the author’s original community. It was their lived-in reality. It illustrates the aphorism that though the Bible has been written for us it was not written to us. The psalm evidently had significant meaning and impact so the believing community of the era used the psalm and included it in their worship repertoire.

129. So it became part of the Bible, the Word of God. The message of the psalm is not unique as the idea of ‘dwelling in Yahweh’ is a theme that has parallels throughout Scripture. For example Paul wrote, ‘your life is now hidden with Christ in God’ (Colossians 3:3) and he writes about, ‘him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to his power that is at work within us’ (Ephesians 3:20).

130. A similar message appears in other psalms too:

Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, my Saviour and my God (Psalm 42:5).

My soul finds rest in God alone; my salvation comes from him. He alone is my rock and my salvation; he is my fortress, I will never be shaken (Psalm 62:1-2).

131. This message is repeated in Habakkuk 3:17-19:

Though the fig tree does not bud and there are no grapes on the vines, though the olive crop fails and the fields produce no food, though there are no sheep in the pen and no cattle in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in Yahweh, I will be joyful in God my Saviour. Sovereign Yahweh is my strength; he makes my feet like the feet of a deer, he enables me to go on the heights.

132. Habakkuk’s, ‘Sovereign Yahweh is my strength’ statement, is a variation of the phrase ‘living by faith’ that expresses his testimony that he can see beyond impending starvation and destitution. He is moved to declare that there is something richer and more important in life: finding purpose, direction and fulfilment in Yahweh.

133. Similarly, in Psalm 91, the psalmist shares his experiences, insights and wisdom to guide and encourage his readers. He too calls on believers to focus on Yahweh for their security and guidance throughout life.

134. He does this using metaphors in the same way that Jesus used parables and is described in Psalm 78:1-7:

O my people, hear my teaching; listen to the words of my mouth. I will open my mouth in parables, I will utter hidden things, things from of old – what we have heard and known, what our fathers have told us. We will not hide them from their children; we will tell the next generation the praiseworthy deeds of Yahweh, his power, and the wonders he has done. He decreed statutes for Jacob and established the law in Israel, which he commanded our forefathers to teach their children, so the next generation would know them, even the children yet to be born, and they in turn would tell their children. Then they would put their trust in God and would not forget his deeds but would keep his commands.

135. The psalmist appears to have come to a stage in life where he is at peace. He reflects on his life and describes the troubles, crises and fearful situations he had experienced. He sees them in the light of the assurance all believers have of the presence of Yahweh to guide, control and move powerfully in our lives.

136. The psalmist is reminded of times of danger and confusion when his life was at risk and his family and community were in danger. Life as he knew it was falling apart. But rather than focus on these troubles, as happens in other psalms such as Psalms 5, 11 and 58, he focusses on Yahweh and the assurance his presence and care has provided.

137. The lessons he has learned are expressed in this psalm of insight and hope that is intended to encourage others on their own journey through the troubles of life.

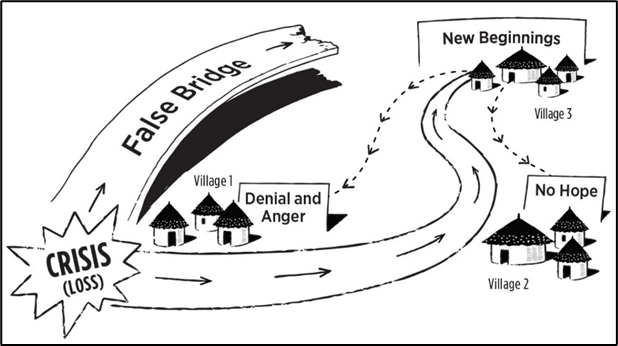

138. We too go through troubles in life and they can cause trauma – which is the adverse reactions we experience as a result of those troubles. We may go through the same trouble as others do but we react differently. Equally, we may go through a similar experience on more than one occasion but may react differently on each occasion. A helpful model to aid understanding of the recovery from such trauma-causing experiences is the Journey of Grief.

139. Descriptions of experiences on this journey[14] feature in lament psalms. The early stage in the ‘Village of Denial and Anger’ is illustrated in Psalm 137 and Psalm 79 while the ‘Village of No Hope’ appears in Psalm 88. Here in Psalm 91 is a description by someone who has arrived at the Village of New Beginnings (see also Psalm 147). He looks back over his life without bitterness or regret as he understands his experiences have been aspects of the way he has lived by faith, or, as he expresses it, dwelling in Yahweh.

140. This process for the believer is an aspect of salvation though it is not about conversion or obtaining eternal life. Rather, it is about the continuing experience of salvation throughout the believer’s life between conversion and eternity. This includes being protected from imminent danger (strophe A), and sometimes that happens dramatically (strophe A1). On other occasions it is expressed as being hidden from danger (strophe A) or being rescued in times of deathly stress and fear (strophe B) or even being preserved from danger with Yahweh’s help (strophe C). A study of NT ‘salvation’ words that relate to this continuing experience of salvation is explored in Theology of Trauma Healing.

141. Is this not true to life? However, in our developed world where there is so much support and so many options there is a very real danger we only ‘need’ Yahweh and turn to him when all else fails.

142. Psalm 91 is therefore a call to us to come back to basics, to ensure we are ‘dwelling in Yahweh,’ living by faith and allowing Yahweh to be our all-sufficient strength, comfort and wisdom. As we do so we will enjoy a richer and deeper experience of God’s continuing work of salvation in our lives.

Endnotes

[1] My main sources of information are J. D. Douglas, and others, (Ed.) The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1980), Hershel Shanks, (Ed.), Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1999) and Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions, trans. by John McHugh (Trowbridge: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1973).

[2] Hershel Shanks, Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman Destruction of the Temple, pp. 163-164.

[3] G. G. Garner, ‘Fortifications and Siegecraft, The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, pp. 522-526.

[4] Oded Borowski, Five Ways to Defend an Ancient City: An examination of city fortifications in the ancient Near East, https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/archaeology-today/biblical-archaeology-topics/biblical-archaeology-basics/bar-jr-five-ways-to-defend-an-ancient-city/?mqsc=E4141842&dk=ZE212CZF0&utm_source=WhatCountsEmail&utm_medium=BHDA%20Daily%20Newsletter&utm_campaign=2_11_22_Five_Ways_to_Defend_an_Ancient_City, [accessed 22 February 22].

[5] William D. Mounce, Mounce’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words, (Grand Rapids, MI., Zondervan, 2006), p. 717.

[6] D. R. Hall, ‘Animals of the Bible,’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 61.

[7] D. R. Hall, ‘Animals of the Bible,’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 62.

[8] J. A. Thompson, ‘Snare,’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 1466.

[9] Christians who are involved in relief ministries after catastrophic disasters know well that spiritual ministries (that are included in Maslow’s aesthetic, self-actualisation and transcendence categories of need) are appreciated as much as, or even more, than the practical help in supplying food, water and accommodation. Now it is widely acknowledged in the scientific community that Maslow’s hierarchy of need is not based on research and does not express the true reality of human behaviour and interests when in desperate need. However, this appreciation has not yet seeped into the popular media and some teaching establishments. For an introduction to this topic see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs [accessed 9th September 2022].

[10] Rev. Dr. A. Cohen, The Psalms: Hebrew Text, English Translation and Commentary, (Chesham: The Soncino Press, 1945), p. 303.

[11] G. S. Cansdale, ‘Animals’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, pp. 58 and 64.

[12] G. S. Cansdale, ‘Animals,’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, pp. 58-59.

[13] G. S. Cansdale, ‘Animals,’ in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 64.

[14] Dana Ergenbright and others, Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help – Stories from Africa, (Participant Book for Healing Groups), revised edn (Philadelphia, PA: SIL International and American Bible Society, 2021), p. 37.

Written: 10 July 2020

Published: 7 April 2024

Updated: 16 April 2024