Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light for my path. (Psalm 119:105)

Psalm 88 (NIV)

A song. A psalm of the Sons of Korah. For the director of music. According to mahalath leannoth. A maskil of Heman the Ezrahite.

1 O LORD, the God who saves me, day and night I cry out before you. 2 May my prayer come before you; turn your ear to my cry.

Persistent requests and demands to be heard.

3 For my soul is full of trouble

and my life draws near the grave.

4 I am counted among those who go down to the pit;

I am like a man without strength.

5 I am set apart with the dead,

like the slain who lie in the grave,

whom you remember no more,

who are cut off from your care.

Senses his life is coming to an end because of all his troubles.

6 You have put me in the lowest pit,

in the darkest depths.

7 Your wrath lies heavily upon me;

you have overwhelmed me with all your waves. Selah

8 You have taken from me my closest friends

and have made me repulsive to them.

I am confined and cannot escape;

9 my eyes are dim with grief.

Blames Yahweh for all the bad things that are happening.

I call to you, O LORD, every day; I spread out my hands to you. 10 Do you show your wonders to the dead? Do those who are dead rise up and praise you? Selah 11 Is your love declared in the grave, your faithfulness in Destruction? 12 Are your wonders known in the place of darkness, or your righteous deeds in the land of oblivion?

Appeals for Yahweh’s attention reminding Yahweh that he will not be able to respond once he is dead.

13 But I cry to you for help, O LORD; in the morning my prayer comes before you. 14 Why, O LORD, do you reject me and hide your face from me?

Senses that Yahweh is deliberately ignoring him.

15 From my youth I have been afflicted and close to death; I have suffered your terrors and am in despair. 16 Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me. 17 All day long they surround me like a flood; they have completely engulfed me. 18 You have taken my companions and loved ones from me; the darkness is my closest friend.

His life-long troubles will soon be over so all he can look forward to is death and darkness.

As an introduction

to Psalm 88 here is a 22-minute videoed talk:

Notes

1. Psalm 88 is a lament psalm of utter despair that focuses on death – ‘death’ and related words are used 17 times in 18 verses/294 words.

2. Lament psalms normally feature a complaint that is invariably addressed to God and end with a declaration of trust and commitment. This psalm is unusual for 76% of the psalm consists of a complaint and there is no concluding declaration of trust. Of the eleven lament psalms I have investigated in detail this complaint is nearly twice as long as in any other lament psalm.

3. There is a very brief review of Yahweh’s previous faithfulness but the references are scattered throughout the psalm so are easily missed.

4. His only request is that Yahweh listens to him. He does not request the resolution of his problems or retribution on those who have caused his troubles. He just wants to be heard. Nothing more, but equally nothing less. This plaintive cry emphasises the psalmist’s loneliness and despair.

5. The concluding phrase, ‘the darkness is my closest friend,’ is a significant factor in this psalm being described as the ‘gloomiest’[1] of psalms or ‘there is no sadder prayer in the Psalter’[2] with ‘no gleam of light or hope.’[3]

6. Nevertheless, the psalm is introduced with the phrase, ‘O Yahweh, the God who saves me.’ That acknowledgement of God’s faithfulness and dependability displays the psalmist’s awareness of God’s presence even though he is distraught by his parlous situation. A vow at the end may well have been overwhelmed by the depth of sorrow and despair the psalm contains but being the introduction all that follows has to be understood in the light of his confidence that God is an active Saviour – notice that the present tense is used.

7. On the other two occasions that he cries out to God the present tense is used again: ‘I call to you, O Yahweh, every day’ (9) and ‘but I cry to you for help, O Yahweh’ (13). The psalmist is not resting on his past experiences or hopes for the future. He has an active, present-day trust in Yahweh.

8. On each occasion God is addressed by name as Yahweh, though NIV and most other versions use ‘LORD’ following a Jewish tradition that Yahweh was too holy a name to pronounce. The use of capitals distinguishes it from ‘Lord’ that translates Adonay. Yahweh means the one who was, is and forever will be. That is God’s personal name and is the way God is usually addressed in OT. It recognises that Yahweh is the ‘always I am,’ he is ever present and available. And God is addressed by name! He is known. There is a relationship, a personal relationship (and see paragraphs 22-23).

9. The other positive observation is that the psalmist continues to pray even though he believes that God is not listening (2) and is even deliberately ignoring him (14). That suggests that even in the appalling situation strongly hinted at but not explained, the psalmist was still fully aware that his hope and salvation lay in God.

10. Psalm headings are generally regarded as less significant than the psalm text by Christian scholars but in the Hebrew Bible they are counted as verse 1, so the Hebrew verse numberings do not match Christian translations. They are very ancient, even if not part of the author’s text. It is impossible to discover exactly when they were introduced. This one provides more details than usual so is worthy of comment.

11. The psalm is called both a ‘song’ and a ‘psalm.’ A further 12 psalms[4] have this dual identification. The Hebrew word for psalm, mizmor, means melody while song/sing is ‘sir.’ The distinction would have been meaningful to the original songwriter and his people but it is no longer understood as far as I can discover.

12. The ‘Sons of Korah’ wrote 11 psalms.[5] They were presumably descendants of Korah, the great-grandson of Levi (Exodus 6) who led a rebellion against Moses (Numbers 16) so it is instructive to note they kept their role in spite of their ancestor’s rebellion – an illustration of God’s forgiveness and refusal to hold a grudge. Their Psalms 48, 84 and 87 seem to refer to Temple worship in Jerusalem. If so, the family retained their role in leading worship for many generations (Moses to Solomon at least); that is for a minimum of 300 years (though it is possible these may be more ancient psalms that were later edited to include reference to Temple worship).

13. ‘Mahalath leannoth’ is a literary or musical term. Cohen translates it as ‘sickness to afflict,’ that refers to the name of a melody;[6] Amplified Bible as, ‘set to chant mournfully.’

14. ‘Maskil’ is once translated as ‘psalm of praise’ (Psalm 47 introduction) while it is left untranslated on 13 occasions. Goodrich suggests it means, ‘wisdom song.’[7]

15. One might expect worship leaders to come from the tribe of Levi, the priestly tribe (1 Chronicles 15:16-22), but Heman the Ezrahite is of the tribe of Judah (1 Chronicles 2:6). He is not one of the ‘Sons of Korah.’ Psalm 88 is his only attributed psalm and Psalm 89 is attributed to his brother Ethan. They, with their brothers Calcol and Darda were so renowned for wisdom that Solomon was compared to them (1 Kings 4:30-31). A different Heman,[8] who was descended from Korah is mentioned in 1 Chronicles 6:33, 15:17 and 19, 16:41-42, 25:4-6 though Kidner claims they could be the same person.[9]

16. It is unusual to have multiple authors acknowledged in the heading. The reference to Heman’s wisdom makes me wonder if he wrote the lyrics while the sons of Korah composed the music.

17. Notes 10-16 about the heading have little meaning for us but they provide evidence about the high regard for psalm-writers and musicians in ancient Israel. The use of descriptive terms such as, ‘Mahalath leannoth’ and ‘Maskil’ indicate that there was a well-developed style in music and singing that was reproducible over subsequent generations even though nearly 3,000 years later we no longer understand these terms.

18. If psalms were held in such high regard might this suggest there would have been a comparable high regard for Scripture too?

19. The OT narrative, especially in Kings and Chronicles focuses on the shortcomings, wickedness and apostasy of the kings and their advisers and sometimes the nation as a whole. In Josiah’s reign ‘the Book of the Law’ was found (2 Kings 22-23) and it appears to take even the priests by surprise as if they did not know such a book existed. However, these details about the psalms suggest there may well have been a core of devoted followers of Yahweh throughout the generations. Perhaps it was not only Elijah’s generation that had, ‘seven thousand in Israel – all whose knees have not bowed down to Baal and all whose mouths have not kissed him’ (1 Kings 19:18).

20. To return to the text of the psalm.

21. Notice the emphasis on himself. ‘I,’ ‘me’ and ‘my’ are used 34 times in the 294 words of the Psalm. This personal focus and a focus on the negative aspects of the situation are features of the grief reaction to trauma.

22. Although the psalmist is obsessed with his own death-like situation he does address his concerns to God. Including the 4 mentions of his name, Yahweh, he refers to God 32 times. However, he says nothing about God except his assertion, ‘the God who saves me’ (1). Otherwise, he refers to God only in regard to his own suffering.

23. But he speaks about more than his concerns – there are two sections in which the psalmist blames God for his troubles:

6 You have put me in the lowest pit, in the darkest depths. 7 Your wrath lies heavily upon me; you have overwhelmed me with all your waves. Selah 8 You have taken from me my closest friends and have made me repulsive to them. I am confined and cannot escape; 9 my eyes are dim with grief. 15 From my youth I have been afflicted and close to death; I have suffered your terrors and am in despair. 16 Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me. 17 All day long they surround me like a flood; they have completely engulfed me. 18 You have taken my companions and loved ones from me; the darkness is my closest friend.

24. Theodicy is the part of Christian belief which is about explaining how a good, compassionate, almighty, and all-knowing God can permit the presence of evil. The Bible, however, has no qualms about God being blamed for tragedies and evil – as in this psalm. After all, if God is the ultimate authority he is ultimately responsible too. But that in itself does not give any right to his created beings to question God as if he can be called to account; though such challenges do occur in Scripture as here. Not that the Bible commends these complaints. Not at all. But the Bible says it as it is. People, believers included, do blame God for their misfortunes. It is a feature of the Journey of Grief. It does not necessarily point to a loss of faith or apostacy, though it can lead to that.

25. Remember Job. He suffered appallingly. We know the reason as we also read the back story but Job never learns about that. At the end of the book God speaks to Job but he does not apologise, excuse or explain. He demonstrates to Job his power and glory and Job is the one who apologises and submits in worship.

26. I think that one of the most powerful and central depictions of the character and nature of God is in Hosea 11. That demonstrates God’s love and compassion even when neglected, abused and dishonoured.

27. All this suggests that God is not a remote and uncaring God. He is compassionate and empathetic and shares in our grief and pain.

28. God identified with suffering humanity in the coming of Jesus:

… Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death – even death on a cross! (Philippians 2:5-8).

29. That tells us not only about Jesus’ love but also about God’s love and character. This is the same God who features in the OT.

30. We need to bear this in mind as we consider this psalm that is all about bad things that happen to believers.

31. The psalm is dominated by death so before analysing the psalm we need to reflect on this topic, for what the psalmist says about death is an aspect of his cultural understanding. Here, the sixteen relevant words are highlighted and the Hebrew original is included:

3 For my soul is full of trouble and my life draws near the grave (sheol). 4 I am counted among those who go down to the pit (bor); I am like a man without strength. 5 I am set apart with the dead (mut), like the slain (halal) who lie in the grave (qeber), whom you remember no more, who are cut off (gazar) from your care. 6 You have put me in the lowest pit (bor), in the darkest depths (mesola). 10 Do you show your wonders to the dead (mut)? Do those who are dead (repaim) rise up and praise you? Selah 11 Is your love declared in the grave (qeber), your faithfulness in Destruction (abaddon)? 12 Are your wonders known in the place of darkness (hosek), or your righteous deeds in the land of oblivion (nesiyya)? 15 From my youth I have been afflicted and close to death (gawa); I have suffered your terrors and am in despair. 18 You have taken my companions and loved ones from me; the darkness (mahsak) is my closest friend.

32. The sixteen words used are in three categories: death, after death and metaphor.

33. Death

| Verse | Word | Notes |

| 15 | Close to death Gawa | = Perish, die, breathe one’s last breath x 24 The end of life. |

| 5, 10 | The dead Mut (verb) | = Die, dead x 847. Cf Mawet (noun) = death x 151 Life is ended. The opposite of the living. Death (mawet) could be personified but there is still no hint this is acknowledging Mut, the Canaanite god of death. Death (mawet) has climbed in through our windows and has entered our fortresses; it has cut off the children from the streets and the young men from the public squares (Jeremiah 9:21). “I will ransom them from the power of the grave (sheol); I will redeem them from death (mawet). Where, O death (mawet), are your plagues? Where, O grave (sheol), is your destruction?” (Hoses 13:14). …indeed, wine betrays him; he is arrogant and never at rest. Because he is as greedy as the grave (sheol) and like death (mawet) is never satisfied, he gathers to himself all the nations and takes captive all the peoples (Habakkuk 2:5). |

| 5, 11 | The slain Halal | = Dead, slain x 92 Halal seems be used to refer to a violent death (slain, killed, slaughtered). |

| 5, 11 | The grave Qeber | = Tomb, grave x 68 Qeber is the physical place where bodies are placed after death (Numbers 19:16, 1 Kings 13:31). In Israel this was in a cave either natural (Genesis 23:20) or man made (Isaiah 22:15-16) though what seems to have been a communal grave was available for ‘common people’ (2 Kings 23:6). It is occasionally used metaphorically (Psalm 5:9). |

34. These words tend to focus on the physical aspects of death at the end of life. Mut (verb) and mawat (noun) are commonly used. On occasion there seems to be some cross over of meaning compared to sheol so it may be used to refer to the continuing state of death. Halal is used to describe violent death and qeber refers to the tomb or burial chamber where bodily remains are respectfully stored.

35. After death

| Verse | Word | Notes |

| 3 | The grave Sheol | = Grave, death x 66 Sheol is translated as grave (x 55), but also as death, depths, depths of the grave and realm of death. This is a the common word that refers to the state of death. We need to be wary of reading into it more than is warranted. At death people were buried (in caves) so sheol is ‘down,’ in the ‘depths.’ It is the end of life. However on a few occasions there is a hint that there might be something else. Maybe an afterlife – or is it only poetic personification? There is a vague hope of something special that Job seems to catch some progressive glimpses of (Job 14:10-13, Job 17:11-16, Job 19:23-27 – see notes 37 and 40). Sheol is capitalized in some translations as if it is a specific place. I do not think there is any hint of that in Scripture. Canaanite and other religions did seem to have this concept and so would have a god in charge. I think Scripture is therefore careful not to indulge in superfluous information that could be taken to support unbiblical ideas. |

| 10 | Dead Repaim | = Dead x 5, spirit of the dead/departed x 3. Repaim is used when the dead are personified by giving them features that only the living have and the dead cannot have. It should not be assumed that it suggests the possibility of the dead having some form of life that the use of ‘spirit’ might suggest. Using ‘spirit’ is a contextual translation. It is nothing to do with ruah the life-spirit. The texts make equal sense if it is assumed that the dead no longer exist. |

36. Sheol, although usually translated as grave, does not refer to the resting place of dead bodies. It seems to be more about a place where existence is ‘no more’ but nevertheless it is where there is a gathering together with forefathers, or even with children who have died prematurely. However, there is occasionally a reference to consciousness that could be a personification metaphor so should not be treated factually. For example see:

The grave (sheol) below is all astir to meet you at your coming; it rouses the spirits of the departed (repaim) to greet you (Isaiah 14:9).

More often it is the absence of the normal features of life that are described:

No one remembers you when he is dead. Who praises you from the grave(sheol)? (Psalm 6:5).

…in the grave (sheol), where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom (Ecclesiastes 9:10).

For the grave (sheol) cannot praise you, death (mawet) cannot sing your praise; those who go down to the pit cannot hope for your faithfulness (Isaiah 38:18-19).

37. It is not relevant to Psalm 88 but it is fascinating to see how a few OT writers reflect on death in the light of what they know of God’s character, grace and concern for his creation and begin to think that there could well be the possibility of a resurrection life. Job seems to catch a glimpse of this (Job 14:10-13), he later realises there just has to be something better (Job 17:11-16) and later still he grasps the New Testament reality – his hope is in his Redeemer-God not in himself or a vagary of chance (Job 19:25-27)! Other writers seem to have a similar glimpse:

…therefore my heart is glad and my tongue rejoices; my body also will rest secure, because you will not abandon me to the grave (sheol), nor will you let your Holy One see decay. (Psalm 16:9-10). Note that this text is used messianically in NT so the translators seem to have transposed that interpretation to the source text. Elsewhere the word translated as ‘Holy One’ becomes saint, faithful one or godly. He is still referring to himself.

But God will redeem my life from the grave (sheol); he will surely take me to himself. (Psalm 49:15).

The path of life leads upward for the wise to keep him from going down to the grave (sheol). (Proverbs 15:24).

I will ransom them from the power of the grave(sheol); I will redeem them from death (mawet). Where, O death (mawet), are your plagues? Where, O grave (sheol), is your destruction? (Hosea 13:14).

And then to confirm these glimpses Isaiah 25-26 speaks prophetically and God reveals even more of his plans in Daniel 12.

38. Metaphors

| Verse | Word | Notes |

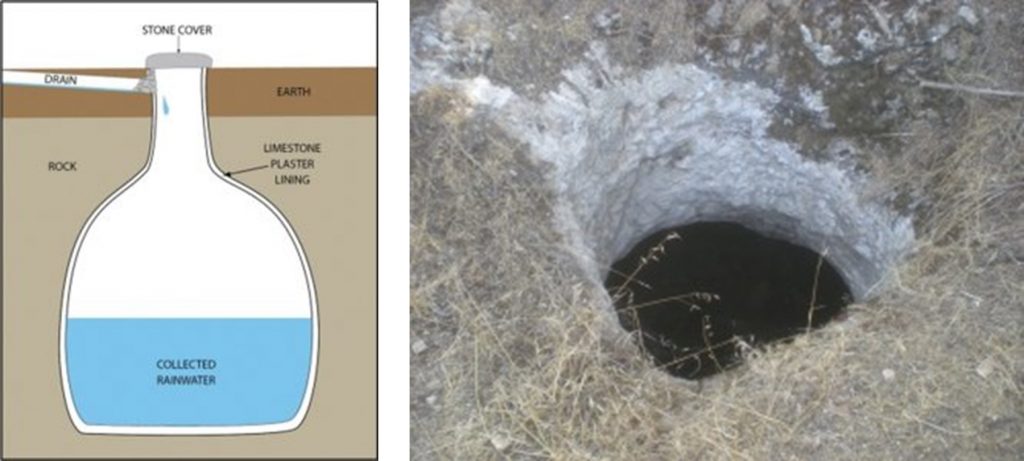

| 4, 6 | The pit Bor | = Pit, well, cistern, dungeon. x 70 Pits (bor) were dug (Exodus 21:33) as wells (2 Samuel 23:15) to store water (cisterns) and as traps (2 Samuel 23:20) but could be used as prisons (Genesis 37:22-24, Jeremiah 38:6-13) so naturally could be used as a metaphor for death and the grave (Psalm 30:3, Isaiah 14:15, Jeremiah 26:19-21). |

| 11 | Destruction (abaddon) | x 11. = Destruction x 5. Some translators leave it untranslated as if it were a place name. Related to abad destroy x 187. Rarely used. Synonym of death/the grave. There is no OT evidence of it being seen as a specific place or situation so I do not see why it is capitalized. In Job 31:12 ‘Destruction’ refers to a fire that consumes completely so it is nothing to do with death. In the other four occurrences (Job 26:6, Job 28:22, Psalm 88:11 and Proverbs 15:11) it is paired with death (sheol) twice, death (mowet) and the grave (qeber) indicating that it is to be seen as a poetic parallel and adds emphasis to the idea that it is the destructive aspect of death that the writer has in mind. I do not recognise any hint that it refers to a specific place. Abaddon in the vision in Rev 9:11 is the name of the satanic(?) angel in charge of the Abyss but that is not related to the OT use of abaddon. |

| 6 | The (darkest) depths Mesola | = Depths x 9 Metaphor implying that the dead are far away, buried and irrecoverable. |

| 12 | The (place of) darkness Hosek | = Darkness, gloom associated with ignorance and despair x 80. Metaphor that expresses a sense of death being the absence of light and life so there can be no awareness and ability to do anything. |

| 12 | the land of oblivion Nesiyya | = Oblivion, place forgotten x 1. A metaphor about being unaware or of being forgotten. Only used this once. |

| 5 | are cut of Gazar | = Cut in two, divide, excluded x 12. Metaphor emphasizing separation, it is final, there is no possibility of rejoining life. |

| 18 | The darkness Mahsak | = Place of darkness, hiding place x 7. Similar to hosek that expresses a sense of death being the absence of light and life so there can be no awareness and ability to do anything. |

39. The Bible is not a theological textbook so there is no developed ‘doctrine’ about death. Death is described in the light of the individual writer’s cultural understanding. However, the overall impression of the Bible’s message is that death means life is over. There is nothing more: ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’[10] summarises the OT understanding of death. There is no evidence of a sensate spirit life after death such as features in contemporaneous religions.

40. However, there are a few glimpses of hope. They come, not from unearthing some secret knowledge but from those who seek God and develop an awareness of Yahweh’s character. The glimpses described develop into an assurance in ‘my Redeemer’ (Job 19:25), ‘The Sovereign Yahweh’ (Isaiah 25:8) and ‘the Lord God’ (Daniel 9:15 re chapter 12). The glimpses of a resurrection life, a judgment and hints of a new heaven and a new earth are a foretaste of NT revelations.

41. The Bible is not concerned about developing our knowledge of or understanding about death or anything else. Rather, it is about us developing a relationship with God as Redeemer, Yahweh and Lord God.

42. These details provide insights into the world of the author. These are the features he would have in mind when he refers to death and they may well be quite different to our own cultural assumptions and understanding of Scripture as we reflect on all that the Bible says. In contrast, the psalmist was living within its pages so only knew what he reveals he knew. We need to bear these definitions and comments in mind as we consider what the psalmist writes as we turn to the poetic structure.

43. The NIV layout is based on ‘subject matter’[11] which is an English style of writing poetry but that is not how Hebrew was laid out.

44. Hebrew poetic lines are in two parts with the second part shown by line indentations as in Bible translations such as NIV and NRSV.

45. In this psalm the lines are arranged in strophes; all are couplets and each is about an idea that is shown below, in the second column.

46. Each idea contributes to the theme of the stanza as shown in the stanza heading. These themes are part of the overall theme of the psalm that is shown in the title, ‘The Desolation of Severe and Prolonged Trauma.’

47. The next feature of the structure of Hebrew poetry is parallelism but this is distinctly different to the rhyming and rhythm parallelism of English poetry.

48. Parallelism in Hebrew poetry concerns the idea being expressed. The words may change but the idea being expressed is repeated, contrasted or developed. In Psalm 88 the parallelism is between the stanzas rather than within them. This is indicated with the letter/number at the head of each line. A-A1, B-B1 etc are paired.

49. Each strophe in Stanza 1 addresses a different aspect of the theme of the Psalm – the desolation that results from severe and prolonged trauma while the Stanza 2 strophes express the same idea but more stridently and aggressively.

50. Hebrew psalm structure is a simple but brilliant style as these features are therefore translatable into other languages. I think it must have been one of the reasons God designed Hebrew as the original language of the Old Testament!

Psalm 88 (Hebrew poetic structure)

The Desolation of Severe and Prolonged Trauma

| Stanza 1 | The Psalmist’s complaint | |

| X | 1 O Yahweh, the God who saves me, day and night I cry out before you. 2 May my prayer come before you; turn your ear to my cry. | Demands Yahweh’s attention. |

| A | 3 For my soul is full of trouble and my life draws near the grave. 4 I am counted among those who go down to the pit; I am like a man without strength. | Trapped. |

| B | 5 I am set apart with the dead, like the slain who lie in the grave, whom you remember no more, who are cut off from your care. | Forsaken. |

| C | 6 You have put me in the lowest pit, in the darkest depths. 7 Your wrath lies heavily upon me; you have overwhelmed me with all your waves. Selah | Overwhelmed. |

| D | 8 You have taken from me my closest friends and have made me repulsive to them. I am confined and cannot escape; 9 my eyes are dim with grief. | Lonely |

| Stanza 2 | Complaint stridently repeated | |

| X1 | I call to you, O Yahweh, every day; I spread out my hands to you. 10 Do you show your wonders to the dead? Do those who are dead rise up and praise you? Selah | Challenges Yahweh to respond as his death is immanent. |

| A1 | 11 Is your love declared in the grave, your faithfulness in destruction? 12 Are your wonders known in the place of darkness, or your righteous deeds in the land of oblivion? | Trapped. |

| B1 | 13 But I cry to you for help, O Yahweh; in the morning my prayer comes before you. 14 Why, O Yahweh, do you reject me and hide your face from me? | Forsaken. |

| C1 | 15 From my youth I have been afflicted and close to death; I have suffered your terrors and am in despair. 16 Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me. | Overwhelmed. |

| D1 | 17 All day long they surround me like a flood; they have completely engulfed me. 18 You have taken my companions and loved ones from me; the darkness is my closest friend. | Lonely |

51. Now to examine the strophes in more detail.

52. Strophe X introduces the first stanza but it is labelled X rather than A as it is the key to understanding the stanza, just like the X strophe in the centre of a chiastic psalm.

X 1 O Yahweh, the God who saves me, day and night I cry out before you. 2 May my prayer come before you; turn your ear to my cry.

The psalm is addressed to Yahweh, and acknowledges that he is the God who plays an active and current role in the psalmist’s life as Saviour. To him he prays day and night, crying out ceaselessly. He lacks assurance so pleads to be heard in a brief and unusually polite (for lament psalms) request, ‘May my prayer come before you.’ It is repeated as a demand, ‘turn your ear to my cry’ which is the not uncommon way requests are made in the lament psalms.

53. In the first stanza the complaint occupies all but the first two lines. The psalmist has many unspecified troubles that make him feel his life is coming to an end and he believed that everyone else agreed about that. There is no way of stopping it.

54. To him it seemed as if he were heading for a pit (strophe A). These were dug commonly for water storage but they could be used for storing grain or even as trap for animals or as a dungeon as happened to Joseph (Genesis 37:24).

A 3 For my soul is full of trouble

and my life draws near the grave.

4 I am counted among those who go down to the pit;

I am like a man without strength.

They were deep and dark and once in, it would be impossible to escape. He was trapped. A powerful metaphor for death.

55. Strophe B describes death as featuring a sense of being forsaken, no longer remembered and cut off from any possible assistance.

B 5 I am set apart with the dead, like the slain who lie in the grave, whom you remember no more, who are cut off from your care.

56. Strophe C describes how he was trapped and forsaken in a pit that was deep and dark, and beyond any help – yet something reached him – it was God’s wrath! It was heavy, weighing him down and felt like wave after wave of stormy seas crashing over him so he could not rise and take a breathe. He was overwhelmed.

C 6 You have put me in the lowest pit, in the darkest depths. 7 Your wrath lies heavily upon me; you have overwhelmed me with all your waves.

57. The psalmist does not explain what had made him like this but it was something that had taken him from his friends and caused his friends to find him repulsive (strophe D). His loneliness has added to his sense of isolation and entrapment. He weeps persistently so his eyelids are swollen and his vision is blurred as he is overcome with anguish and grief.

D 8 You have taken from me my closest friends and have made me repulsive to them. I am confined and cannot escape; 9 my eyes are dim with grief.

58. The second stanza parallels the first but adopts a more aggressive tone. His complaints are presented as rhetorical questions which add to the aggressiveness.

59. In strophe X1 the psalmist again addresses Yahweh. He insists he prays ‘every day’ with hands spread out in supplication. His frustration at Yahweh’s silence bursts out in two aggressive rhetorical questions:

X1 I call to you, O Yahweh, every day;

I spread out my hands to you.

10 Do you show your wonders to the dead?

Do those who are dead rise up and praise you?

60. ‘Do you show your wonders to the dead (mut)?’ implies, ‘The dead are dead. They cannot appreciate you but I do. I appreciate you, your power and ability to answer my prayer fully, freely and now! Surely, “my prayer comes before you.”’

61. ‘Do those who are dead (repaim) rise up and praise you?’ implies, ‘The dead cannot stand and raise their hands in worship like I do so if you answer my pleading cry you know very well I will praise and honour you and will tell all I meet about your greatness. Surely, you will “turn your ear to my cry.”’

62. These are examples of how parallelisms (X-X1) can be expressed in the use of opposites.

63. Note too the different words for the dead. Mut is the common word but repaim is used when personification is intended. It adds to the aggressive, mocking tone of the questions. Such rudeness is a common feature of lament psalms.

64. Strophe A1 has are two more rhetorical questions that rephrase the complaint:

A1 11 Is your love declared in the grave, your faithfulness in destruction? 12 Are your wonders known in the place of darkness, or your righteous deeds in the land of oblivion?

The bleakness of death is emphasised by three metaphors that refer to destruction, darkness and oblivion that develop his sense of being trapped, thus paralleling strophe A. They come with a reminder that in death God’s attributes cannot be appreciated. He highlights four:

• love,

• faithfulness,

• his astounding actions in creation and among the believing community

• his righteousness that is expressed in the fulfilment and redemption of that community.

The parallels with strophe A are not obvious except for the link to the grave and the pit. However, the poetically necessary parallel is provided by the contrast between ‘full of troubles’ in strophe A and the fullness of blessing that could be experienced through those four attributes in strophe A1.

65. Perhaps because these attributes are presented negatively they are easy to miss in the sadness and stridency of the complaints but their presence indicates that the psalmist is not entirely focussed on himself and his sufferings. Even in his prolonged anguish he still recognises and values that he is part of a bigger and better world where God’s blessings are richly evident.

66. The first line of strophe B1 is an unexpected break in the litany of complaints as the psalmist repeats his cry to Yahweh for help. This usually would indicate the start of another stanza but there is no other sign of this. The second line is clearly linked with strophe B as ‘reject’ and ‘hide your face’ parallel ‘cut off from your care’ and ‘remember no more’ again emphasising his sense of being forsaken, so it seems it is the authors intention.

B1 13 But I cry to you for help, O Yahweh; in the morning my prayer comes before you. 14 Why, O Yahweh, do you reject me and hide your face from me?

A few other psalms break the poetic pattern similarly. Could this break in pattern be a deliberate ploy to remind singers and readers that our attention should not focus on our troubles, however extensive and serious they are, but on Yahweh, the source of help, stamina and resourcefulness?

67. Strophe C1 matches its parallel C, especially the second line that again refers to God’s wrath that has overwhelmed him like a wave. ‘From my youth’ is a reminder that his sufferings were not only severe but also were prolonged.

C1 15 From my youth I have been afflicted and close to death; I have suffered your terrors and am in despair. 16 Your wrath has swept over me; your terrors have destroyed me.

68. Those overwhelming troubles, whatever they were, had taken all he held dear so he ends poignantly in strophe D1 reflecting that darkness, the epitome of death, was all he had to turn to for support and empathy in his loneliness.

D1 17 All day long they surround me like a flood; they have completely engulfed me. 18 You have taken my companions and loved ones from me; the darkness is my closest friend.

69. This is a sad psalm and it will be hard for anyone to fully empathise with the writer unless they themselves have been through prolonged and severe suffering. Sadly, that is all too common in the world of trauma. And this psalm speaks powerfully into that world. The psalmist speaks of life as it is.

70. That includes the anger, aggression, blame and rudeness toward God and the apparent lack of trust. For those of us who have not experienced devastating trauma such words are hard to bear. But when significant loss, trouble or persecution cause severe trauma it can feel as if God is far away and does not care so such negative complaints addressed to Yahweh are actually a feature of faith and not of unbelief even when expressed as blame and in angry tones.[13]

71. In such cases we are not telling Yahweh what he does not know. He knows what we are thinking and how we feel. He will not be upset when we express such thoughts and feelings. He intends us to do this as it is healthy and releasing. It is the way he created us to behave. And surely, that is an important reason for such lament psalms being included in Scripture.

72. Another difficulty that may be experienced when reading this psalm is based on the human propensity to categorise people so we have difficulty coping when worship and commitment to Yahweh are blended in the same psalm with rude and aggressive complaints and a focus on darkness and despair. It is even worse when we are caring pastorally for a believer who is going through their own Psalm 88 experience and they express Psalm 88 sentiments. ‘You cannot say something like that,’ we protest with shocked horror and treat them guardedly for months afterwards when we meet them in church and see them worshipping happily.

73. It seems likely that this psalm was written by Heman (paragraph 15) but no personal details are revealed either in the psalm or elsewhere in Scripture to help us understand the circumstances and experiences he describes. However, the powerful metaphors and the emotional intensity suggest he is describing his own experiences of suffering. Speculating further is not helpful and the absence of such details means we can more easily allow it to speak into our own situation.

74. Notice too, the psalm does not provide any answers. All it is, is an expression about what it is like to suffer serious and prolonged trauma.

75. Although this psalm is commonly regarded as lacking in any expression of faith or hope,[14] I do not agree. In addition to the point made in paragraph 65, three times Yahweh is invoked (in X, X1 and B1). It is addressed to the ‘God who saves me’ (note 6) and strophe A1 shows an awareness of God’s goodness (notes 64-65).

76. Some commentators suggest this psalm has been written by someone who is terminally ill after a lifetime of illness and suffering, possibly due to leprosy[15] while Kidner suggests it reflects the experience of depressed or outcast people.[16] However, the profuse use of metaphors for death makes me think that even the references to death itself are also used metaphorically to express a death-like situation as can be experienced following a catastrophic loss.

77. To my mind Psalm 88 has a much wider reference as it describes poetically and powerfully the experience on the Journey of Grief when the sufferer passes through the Village of No Hope.[17] Everything is dark and dismal. The sufferer has come to terms with his troubles, whatever they are, in the sense that he has accepted that they have happened so he turns away from being occupied with what he has lost. But he is stuck in the present. He can see no way out. There is no future. He is in a black pit of despondency without a glimmer of hope. But God is still there, or is he? He cries out to God, his Saviour and the God of love and faithfulness who has the ability to help and the righteousness to want to do so. But will he? Even though he feels that God has forsaken him he still cries out.

78. In his lack of faith he still cries out in faith! This is reminiscent of the father of the boy with an evil spirit whom Jesus healed, when he said, ‘I do believe; help me overcome my unbelief!’ (Mark 9:24). It takes seconds to read. Problem solved. Instantaneous. Another success. We move on as did the crowd, and the disciples who wanted to hone their exorcism techniques. But spare a moment to reflect on the trauma that father had been through. His precious, only son who was presumably a young adult at the time (Mark 9:21), had had severe major epileptic-like convulsions that came on without warning for maybe 20 or more years. These attacks caused him to scream, shake violently and fall over and could cause serious injuries as was likely to happen when he fell into an open fire or water. It is likely he was close to death on numerous occasions. The agony of seeing his son suffer. The 24/7 vigilance. Perhaps more than one strong person was needed to help and protect his son in an attack. He may well have neglected other relationships and aspects of life to be available to his son and his consuming needs. The father had evidently persevered faithfully at the thankless task even while watching the crumbling of his hopes for his family’s continuity (his son’s disability would inevitably preclude any prospect of marriage). A dead-end life. Daily struggles just to stand still. He was a Psalm 88 father. He had outlived hope but then he heard of Jesus. His hope was rekindled. Even when Jesus’ assistant healers failed he did not walk away. He still hoped – and then God met him.

And was Abraham another Psalm 88 father? If only he could be a father! As Romans 4:18-21 says,

Against all hope, Abraham in hope believed and so became the father of many nations, just as it had been said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” Without weakening in his faith, he faced the fact that his body was as good as dead – since he was about a hundred years old – and that Sarah’s womb was also dead. Yet he did not waver through unbelief regarding the promise of God, but was strengthened in his faith and gave glory to God, being fully persuaded that God had power to do what he had promised.

We know the end result so can easily dismiss the preceding 70-80 years of unfulfilled hopes and the embarrassment associated with infertility. We can hardly imagine the agony and shame Abraham and Sarah went through year after year. There was no logic in their hope. They were ‘as good as dead’ physically and in Psalm 88 terms, yet they clung on, even though Sarah expressed the doubt-within-faith that Psalm 88 describes (Genesis 18:10-15), and their prayers and hopes were answered.

80. White suggests that Psalm 88 is incomplete and the closing verses that show a returning faith have been lost.[18] That would be a fairy story truth but in a psalm that comes from the reality of trauma such endings may not happen.

81. Although it all came right eventually for Abraham and Mark 9’s father what about the heroes of Hebrews 11?

All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance. And they admitted that they were aliens and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country – a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them (Hebrews 11:13-16).

82. Yahweh is Yahweh. He is not answerable to us but we are answerable to him.

83. He calls us to be faithful and stand with the church in Smyrna,

Do not be afraid of what you are about to suffer. I tell you, the devil will put some of you in prison to test you, and you will suffer persecution for ten days. Be faithful, even to the point of death, and I will give you the crown of life (Revelation 2:10).

84. The Journey of Grief however, continues, so in Psalm 91 we find a believer in the Village of New Beginnings and in Psalm 107 and Psalm 147 we read of whole communities enjoying life in their version of New Beginnings. In God there is hope. There is a future. There is a new start.

85. But having said that, Psalm 88 has been written. It has the passion and understanding of the reality of the Journey of Grief and that suggests to me that the psalmist did come through to live again and was able to write of his experiences while they were still freshly burned into his soul.

86. And such experiences reverberate down the centuries in the experiences of Yahweh’s people:

These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect (Hebrews 11:39-40).

Endnotes

[1] R. E. O. White, A Christian Handbook to the Psalms, (Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1884) p. 135.

[2] Derek Kidner, Psalms 73-150 (Aylesbury: IVP Academic, 2008) p. 348.

[3] Rev. Dr. A. Cohen, The Psalms: Hebrew Text, English Translation and Commentary, (Chesham: The Soncino Press, 1945) p. 285.

[4] Psalms 30, 48, 65-68, 75, 76, 83, 87, 92 and 108.

[5] Psalms 42, 44-49, 84, 85, 87 and 88.

[6] Cohen, The Psalms, p. 285.

[7] Edward W. Goodrick and John R. Kohlenberger III, The Strongest NIV Exhaustive Concordance (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990) ref 5380 p. 1446.

[8] J. G. G. Norman, ‘Heman,’ in ‘The Illustrated Bible Dictionary’ ed by J. D. Douglas (Bungay: Inter-Varsity Press, 1980) p. 265.

[9] Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-73 (Aylesbury: IVP Academic, 2008), p. 50 andDerek Kidner, Psalms 73-150, p. 348.

[10] 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer, based on Gen 3:19 and 18:27.

[11] The Holy Bible (NIV), Popular Cross Reference Edition, 1992, Translators’ Preface, p. x.

[12] Anon, Cisterns in Bible Times, <https://thewaymagazine.com/cisterns-in-bible-times/> [accessed 3 February 2021] and Haber, Joel, ‘What Is… A Cistern?’ From Fun Joel’s Israel Tours, <https://funjoelsisrael.com/2010/09/what-is-a-cistern/> [accessed 21 August 2023]

[13] Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms, (Augsburg, MI: Augsburg Old Testament Studies, 1984) p. 381-382.

[14] For example see Gordon Wenham, The Psalter Reclaimed: Praying and Praising with the Psalms, (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013) p. 44.

[15] White, A Christian Handbook to the Psalms, p. 136 and Cohen, The Psalms, p. 285.

[16] Derek Kidner, Psalms 73-150, p. 348.

[17] Dana Ergenbright and others, Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help, revised edn (Philadelphia: SIL International and American Bible Society, 2021) pp. 32-44.

[18] White, A Christian Handbook to the Psalms, p. 135.

Written: 11 November 2021

Published: 11 April 2023

Updated: 29 August 2023