Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light for my path. (Psalm 119:105)

Psalm 13 (NIV)

For the director of music. A psalm of David.

1 How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? 2 How long must I wrestle with my thoughts and every day have sorrow in my heart? How long will my enemy triumph over me?

Complaint

3 Look on me and answer, O LORD my God. Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death, 4 my enemy will say, "I have overcome him," and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

Request

5 But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation. 6 I will sing to the LORD, for he has been good to me.

Statement of faith

Notes

1. Each line in Hebrew poetry usually has two parts but occasionally three as in verse 2, with the second and third parts repeating, contrasting or developing the first.

2. This is shown in most Bibles by insetting the second and third parts as above.

3. In NIV and most modern translations Psalm 13 is set out in three paragraphs which each have a distinct topic: complaint, request and statement of faith.

4. It is the ‘go to’ psalm to introduce the topic of lamenting.[1] It is concise, clear and illustrates the key parts of a lament psalm.

5. In common with most of the OT, God is addressed as LORD. Spelt in capitals in this form it is nothing to do with ‘Lord’ that translates adonay meaning ‘my Lord,’ and is used of God, gods and people of high rank. LORD stands for Yahweh, the one who was, is and forever will be; that is God’s name. It is not a title. Names are significant in the Bible. ‘Yahweh’ means something like, ‘Always I am,’ for Yahweh lives outside of time. Time is an aspect of creation. With Yahweh everything is ‘now.’ And yet, God is addressed by name! He is known. There is a relationship, a personal relationship. God revealed his name to his people as the name we are to use (Exodus 3:13-15) and so it was. It is, by far, the commonest term used for God in the OT. However, in the period after the OT was completed but before the birth of Jesus, Jewish scholars decided that ‘Yahweh’ was too holy to use so they used adonay instead. This was later adopted by most Christian Bible translators[2] even though it was only a Jewish custom that had no scriptural backing. How sad. What are we missing by this failure to follow Scripture? I am beginning to learn to use God’s name, Yahweh, in prayer and reflection so have decided to use Yahweh instead of LORD in these notes.

6. In spite of knowing all that the name Yahweh stands for, the psalmist starts with a complaint against Yahweh for his neglect and lack of attention! Now that is gross impertinence. In some laments, complaints are softened a little by acknowledging Yahweh’s previous faithfulness and care and sometimes there is a confession of sin or a protestation of innocence; but not here.

7. It gets worse, for although laments occasionally contain polite requests, for example, see Psalms 12:3-4 and 88:2, more often than not imperative verbs are used so they are intended to be demands and not requests. That happens in Psalm 13 where ‘look,’ ‘answer’ and ‘give light’ in verse 3 all take the imperative mood. This is not usually apparent in English translations except a hint may be given by the use of an exclamation mark.[3] There is an element of rudeness, anger, desperation and despair in such demands.

8. In spite of aggressive and self-centred complaints most laments end with an affirmation of trust in God and/or a vow to praise God – in Psalm 13 we have both.

9. This confusing mixture of demands and rudeness on one hand and commitment to serve and praise on the other are features of biblical laments. They accurately reflect the state of mind and spirit of the believer when going through calamitous experiences that lead to trauma.

10. And it is all an expression of faith! [4] That faith is vibrantly alive and active even when circumstances are adverse, hope of deliverance is fading and Yahweh appears to have gone missing. It is the experience of trauma that causes this mixture, NOT a lack of faith.

11. Contrast such a response to unbelievers who may turn against God when they suffer a serious loss, even if they have previously shown little interest in spiritual matters. They may well be angry with God and blame him for their troubles but their antagonism is rarely mollified by any acknowledgement of God’s love and care.

12. Lamenting is as expressive and stunning a demonstration of faith as Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego’s stalwart stubbornness when entering Nebuchadnezzar’s furnace:

Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego replied to the king, “O Nebuchadnezzar, we do not need to defend ourselves before you in this matter. If we are thrown into the blazing furnace, the God we serve is able to save us from it, and he will rescue us from your hand, O king. But even if he does not, we want you to know, O king, that we will not serve your gods or worship the image of gold you have set up.” (Daniel 3:16-18).

13. When aggressively rude complaints as in Psalm 13 are made to Yahweh we are not telling him anything he does not know already. He knows our heart and reads our mind. If we feel like this we can tell Yahweh. We are expressing valid feelings induced by bad experiences. There is no shame in this, though it is appropriate to apologise on later reflection as we move on from the crisis that precipitated our outburst.

14. Studies of this psalm usually end here but there is more to learn in this psalm as we set aside the structure imposed by our understanding of how English poetry functions and consider the structure used by the author.

15. In addition, understanding of the process by which bad experiences cause trauma and how healing and restoration is possible has developed over the last few decades[5] and that too heightens an appreciation of the experiences and insights within Scripture.

16. Both of these facets feature in the following notes.

17. Hebrew poetry is based on parallel ideas – this is not about rhythm or rhyme so features are invariably still recognisable in translation. The idea of each line is summarised in the version below and lines have a parallel line that relates to the same idea.

18. This pattern indicates the psalm has a chiastic structure. There are parallel lines A-A1, B-B1 and C-C1, leaving the ‘punchline’ of the psalm in line X in the centre, at the heart of the psalm. The key words are shown in bold.

Psalm 13

Persevere in faith

| A | For the director of music. A psalm of David. | Commitment to worship. |

| B | 1 How long, O Yahweh? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? | Yahweh’s failure to notice his follower. |

| C | 2 How long must I wrestle with my thoughts and every day have sorrow in my heart? How long will my enemy triumph over me? | The battle is both internal and external. |

| X | 3 Look on me and answer, O Yahweh my God. Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death, | The only source of help is Yahweh. |

| C1 | 4 my enemy will say, “I have overcome him, and my foes will rejoice when I fall. | The battle could be lost. |

| B1 | 5 But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation | The psalmist’s trust and commitment contrasts with Yahweh’s failure. |

| A1 | 6 I will sing to Yahweh, for he has been good to me. | Commitment to worship. |

19. The most obvious parallels are in lines C-C1:

C 2 How long must I wrestle with my thoughts

and every day have sorrow in my heart?

How long will my enemy triumph over me?

C1 4 my enemy will say, "I have overcome him,"

and my foes will rejoice when I fall.

20. Both lines focus on the struggle the psalmist is experiencing with ‘wrestle’ paralleling ‘overcome.’ Line C1 comments about ‘my enemy’ but in line C the adversary is ‘my thoughts.’ That is an insightful description of trauma. It may well be caused by an external problem that has overcome personal resources but equally, trauma may result from an internal struggle as external stresses highlight internal weaknesses. They stimulate memories of previous traumatic experiences and the associated failures and disappointments so there is not only the new experience to deal with, there is also the need to refight old battles.

21. The resultant ‘sorrow in my heart’ parallels (contrasts with) the ‘rejoice’ of the foes at the psalmist’s fall in defeat. And that ‘fall’ parallels the ‘triumph’ of the enemy.

22. But notice ‘will’ and ‘when’ in line C1. The defeat has not yet happened! It is still only in the psalmist’s imagination as he fearfully broods about his appalling situation from which he can see no escape.

23. Only two poetic lines but they pack in a significant amount of information about ‘what happened?’ and ‘how did you feel?’ – two of the three questions the careful listener will use when facilitating someone’s reflection on a traumatic experience.[6]

24. We now turn to lines B-B1:

B 1 How long, O Yahweh? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? B1 5 But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.

25. Here the psalmist compares Yahweh’s secretive (hide your face) forgetfulness with his own trust in him.

26. The psalmist wonders if Yahweh’s forgetfulness will last forever while he, in contrast, revels (my heart rejoices) in Yahweh’s unfailing love and salvation.

27. This is a shocking attitude, for the psalmist reckons he has better morality than Yahweh himself! That demonstrates the arrogance that even the most godly believer can show when traumatised. It can happen to any one of us – that is the effect of trauma for when traumatised our attention is primarily focussed on ourselves.

28. Notice that consideration of the poetic structure gives insight into the meaning of verse 5 that alters the perception of what it first appeared to say (note 8). There is an arrogant bite in the psalmist’s commitment.

29. The final matching pair lines A-A1 is unusual as line A is the title of the psalm and therefore is not usually regarded as part of the psalm but only as a later editorial heading.

A For the director of music. A psalm of David. A1 6 I will sing to Yahweh, for he has been good to me.

30. However, it works poetically as ‘psalm of David’ parallels ‘sing to Yahweh’ and I have been unable to see any other way of completing the poetical structure.

31. Christian commentaries refer to the title of a Psalm as an ancient addition by an unknown editor but it is not considered part of Scripture itself.[7] That certainly often appears to be the case but there may be psalms where the title is original to the author. It looks as if Psalm 13 is one such.

32. Some translations omit the title[8] while others create their own.[9] However, in Jewish translations and commentaries[10] they are accepted as part of Scripture so all titles are included in the text of the Psalm. That means that for those psalms with a title there is a mismatch with the verse numbering compared to Christian translations.

33. When analysing the poetic structure of other psalms I have wondered if the title should be included but this is the first time I have thought it fitted and so was required.

34. English poetic structure requires a ‘perfect’ balance in the rhythm and rhyming and if not achieved the poem will be rated as second class or worse. That does not apply to Hebrew poetry. It is not uncommon to have a break in pattern (for example see Psalm 1 (verse 4), Psalm 91:14 and Psalm 107 (verses 33-42) and this oddity in Psalm 13 may be another example. Such breaks jar with those who are used to English poetic styles but a significant point could be that they are a means of directing attention to the text and its meaning and away from the poet’s skill and flair. They seem to be an essential part of the Psalm as it was originally written.

35. We tend to read this psalm as primarily a complaint so may find it odd for it be sandwiched between these two lines of praise and worship but in Hebrew poetic terms, it keeps the complaint in perspective.

36. I have left the central line to the last as in Hebrew poetry this is the climax, the punchline. Here it is a single line X with no parallel. That draws attention and so emphasises its importance.

X 3 Look on me and answer, O Yahweh my God. Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep in death,

37. After all the anger, doubt and despair and even here, where Yahweh’s attention is demanded, the psalmist recognises his only hope is in Yahweh. But he does not ask for his enemies to be destroyed as in Psalm 5:9-10. Nor does he ask for rescue as in Psalm 6:4. Actually, it is not at all obvious what he does ask for! Whatever does, ‘give light to my eyes’ mean?

38. The Hebrew translated as ‘Give light to my eyes’ is repeated in 1 Samuel 14:27, 29 where it is translated ‘eyes brightened’ as Jonathan refreshed himself during an enemy chase by eating some wild honey. It occurs also in Psalm 38:10, ‘My heart pounds, my strength fails me; even the light has gone from my eyes.’ These are examples of synecdoche, the figure of speech in which a part represents the whole. In this case it uses the observation that when lacking in physical energy eyes lose their brightness. The condition of our eyes is recognised too as a clue to our spiritual state (Psalm 19:8) for Yahweh created us to be whole beings with body, soul and spirit closely integrated. This suggests the psalmist is using this figure of speech to ask for renewed energy and that can affect the whole of his being and not just his eyes.

39. He is aware that he is physically failing, so he asks for strength to continue. What stunning commitment. He intends to persevere in his allegiance to Yahweh even though he can see no future and doubts Yahweh is at all interested in helping!

40. His faith is even more like that of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego than appears at first (note 12). If anything it is even more impressive, for Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego knew that Yahweh was either going to appear in power to rescue them or they would be dead within seconds. However, the psalmist had no idea how long his lonely suffering would continue – but he was still committed.

41. That challenge to commitment no matter what, echoes throughout Scripture and is summarised in Hebrews 11 which ends:

These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect (Hebrews 11:39-40).

Persevering in the darkest of times seems to count more to Yahweh than any ‘successful’ ministry.

42. This is how Paul described his ‘Psalm 13’ experience:

We are fools for Christ, but you are so wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are honoured, we are dishonoured! To this very hour we go hungry and thirsty, we are in rags, we are brutally treated, we are homeless. We work hard with our own hands. When we are cursed, we bless; when we are persecuted, we endure it; when we are slandered, we answer kindly. Up to this moment we have become the scum of the earth, the refuse of the world (1 Corinthians 4:10-13).

43. And Paul expected a similar commitment from other followers of Jesus:

We ought always to thank God for you, brothers, and rightly so, because your faith is growing more and more, and the love every one of you has for each other is increasing. Therefore, among God’s churches we boast about your perseverance and faith in all the persecutions and trials you are enduring (2 Thessalonians 1:3-4).

44. This principle of following Yahweh/Jesus whatever the cost and however hopeless the future appears, applies to Christian believers as well as to the Old Testament people of faith as Hebrews 12:1-13 explains:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses [the Old Testament people of faith described in Hebrews 11], let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles, and let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us. Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy set before him endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God. Consider him who endured such opposition from sinful men, so that you will not grow weary and lose heart.

In your struggle against sin, you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood. And you have forgotten that word of encouragement that addresses you as sons: “My son, do not make light of the Lord’s discipline, and do not lose heart when he rebukes you, because the Lord disciplines those he loves, and he punishes everyone he accepts as a son.”

Endure hardship as discipline; God is treating you as sons. For what son is not disciplined by his father? If you are not disciplined (and everyone undergoes discipline), then you are illegitimate children and not true sons. Moreover, we have all had human fathers who disciplined us and we respected them for it. How much more should we submit to the Father of our spirits and live! Our fathers disciplined us for a little while as they thought best; but God disciplines us for our good, that we may share in his holiness. No discipline seems pleasant at the time, but painful. Later on, however, it produces a harvest of righteousness and peace for those who have been trained by it.

Therefore, strengthen your feeble arms and weak knees. “Make level paths for your feet,” so that the lame may not be disabled, but rather healed.

45. The psalmist adds a final phrase, ‘or I will sleep in death.’ It is as if he feels that due to Yahweh’s lack of response it is likely he will die. He might be expecting that to be at the hand of his adversary who was working toward his ‘fall.’

46. However, the use of the metaphor of ‘sleep’ to refer to his ‘death’ may suggest he is using death itself metaphorically emphasising that his only hope lay in trusting Yahweh. There was nothing else – only sleep, death, finish, the end. He was totally committed.

47. What a powerful witness and testimony is portrayed in this psalm. And this is not expressed in a spirit of humble acceptance. It is based in the stress and anguish of bad experiences that cause the psalmist significant trauma. He speaks from the depth of his trauma with urgent and aggressive complaints that he expresses boldly and without shame.

48. There is no commendation of this behaviour either here or elsewhere in Scripture but being in Scripture, God’s word, there is recognition that this is what happens when godly people are traumatised. This is life as it is. We journey through experiences that cause trauma and here is a description of how the godly believer is likely to respond.

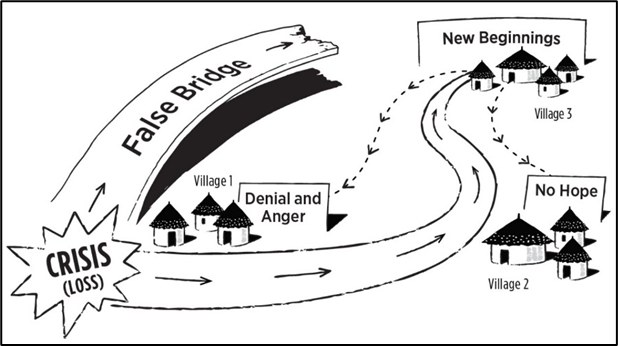

49. But it is only a stage in the Journey of Grief. It is not a permanent condition. We move on. Eventually, the traumas we have suffered are integrated into who we are so, hopefully, we develop more resilience, insight and maturity. This is an aspect of the continuing experience of the salvation that started at conversion and will only be completed in glory.

Endnotes

[1] Dana Ergenbright and others, Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help, revised edn (Philadelphia: SIL International and American Bible Society, 2021), pp. 44-46 and Estes, Daniel J., Handbook on the Wisdom Books and Psalms, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), pp. 165-172.

[2] See for example the Translators’ Preface of NIV 1992 edition.

[3] NRSV, NLT, and Lee M. Fields, Hebrew for the Rest of Us: Using Hebrew Tools without Mastering Biblical Hebrew, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), p. 269.

[4] Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms, (Augsburg, MI: Augsburg Old Testament Studies, 1984) p.52 quoted by Estes, Handbook on the Wisdom Books and Psalms, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), p. 166.

[5] For example see Diane Langberg, Suffering and the Heart of God: How Trauma Destroys and Christ Restores, (Greensboro, NC: New Growth Press, 2015)

[6] Dana Ergenbright and others, Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help, revised edn (Philadelphia: SIL International and American Bible Society, 2021), p. 31.

[7] Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-72 (Aylesbury: IVP Academic, 2008) pp. 47-61, Tremper III Longman, How to Read the Psalms, (Downers Grove, IL.: InterVarsity Press, 1988) pp. 38-42 and Gordon Wenham, The Psalter Reclaimed: Praying and Praising with the Psalms, (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013), pp. 68-71.

[8] Titles are omitted in The Message (except ‘Psalm of David’ is retained), NEB and The Living Bible, for example.

[9] New titles are used in NRSV, Good News and NASB.

[10] Rev. Dr. A. Cohen, The Psalms: Hebrew Text, English Translation and Commentary, (Chesham: The Soncino Press, 1945).

[11] Dana Ergenbright and others, Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help, revised edn (Philadelphia: SIL International and American Bible Society, 2021), p. 36-40.

Written: 2 November 2021

Published: 19 December 2022

Updated: 19 March 2024