I suspect that every language and culture has a special form of writing or talking that is referred to as ‘poetry.’ It expresses thoughts, emotions and impressions and not just facts. It stimulates the reader or listener’s own imagination and emotions so words may be heard and felt almost as much as heard and understood.

Prose is set out in sentences and paragraphs according to rules of grammar. Poetry however, is set out in lines that may not be grammatically correct, even to the extent of omitting words that the reader has to infer. That is one way the reader is drawn in and begins to ‘own’ the poem. Poetry often seems musical – even if not actually set to music – as it has a beat or rhythm. It also has rhyme so lines end with the same sound even though they may have different spellings such as: clay, prey, weigh, bouquet.

Well, that is in English language poetry. It is not easily translated into other languages as rhythm and rhyme are features of language and culture. We might therefore expect that biblical poetic structure will be lost in translation and impossible for anyone without a detailed knowledge of ancient Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek to understand. Stunningly, that is not true![1] However, this paper only deals with the poetry of the Hebrew parts of the Old Testament, though that contains the vast bulk of biblical poetry.

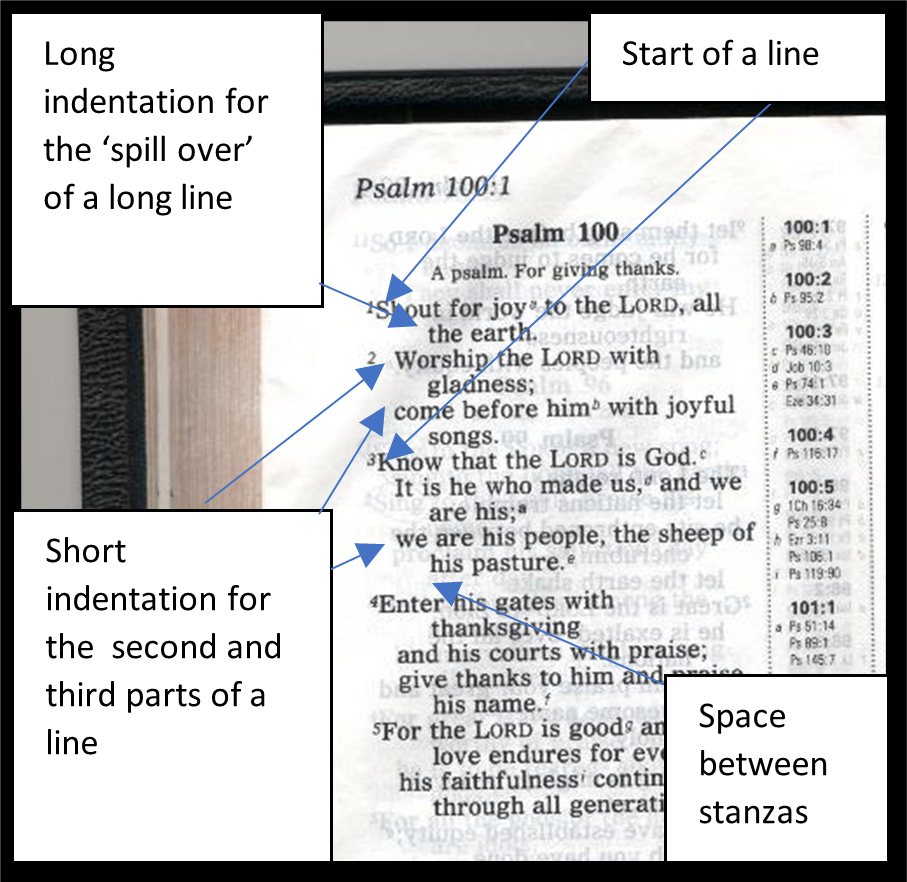

Until the mid-twentieth century the average Bible reader would probably not have known Hebrew poetry existed as the King James Version of the Bible (1611) did not distinguish between prose and poetry. The Revised Version (1885) introduced the indentation of poetic lines setting out every part-line as if it were a full line and then the Revised Standard Version (1952) varied the indentation to indicate a new line or a part line. This ‘line’ is at the heart of Hebrew poetry but ‘line’ does not refer to a line on a page which can vary according to the size of the page. It is a poetic line that is composed of two or more parts and is the psalmist’s creation. As the traditional Bible layout is in columns these are readily shown on separate page lines as shown in the image below. This style was further developed by the New International Version (1978) to include the division of longer psalms into stanzas and for the first time this development was acknowledged in a preface – but who reads that? The New Revised Standard Version (1989) also shows stanza divisions but they are sometimes different to NIV. The NIV preface states, ‘the translators determined the stanza divisions for the most part by analysis of the subject matter.’[2] No account seems to be made of the poetic structure and this is perhaps why often I find a different stanza division suits the poetic structure and meaning of the psalm. Poetic structure is best discerned in English translations that are literal, ‘word for word’ translations such as the NRSV. The NIV is very similar though does sometimes translate a concept rather than the exact words used. Initially I used NRSV as my primary text in these studies but I later changed to NIV (1984) as it is in wider use, had been my preferred translation for some years and I had found very few relevant discrepancies. Translations such as The Living Bible and The Message that use paraphrasing extensively, depend on the translator’s interpretation of poetic features, aspects of Hebrew culture and some metaphors, so are not so helpful. When I came to transpose my written material to a website I decided I should upgrade to NIV (2011) as that is the version commonly used in Bible apps. But that was short lived as NIV (2011) is more of a paraphrased version then previous editions. See Psalm 12 note 5 for an illustration of this.

The scholarly understanding of Hebrew poetry followed a different course. That the Book of Psalms contains 150 numbered psalms was established from time immemorial, though there are a couple of minor variations in ancient Hebrew and Greek versions. In contrast, the division of other Bible books into the modern chapter divisions was only established in the 13th century by Archbishop Langton of Canterbury. Verse numbering for the whole Bible, including the Psalms, as used in most translations, was introduced by Robert Estienne, a French classics scholar and printer, in the 16th century. They are arbitrary divisions and have only an incidental bearing on both the poetic and grammatical structure of Scripture; however, they remain useful for navigating the Bible.

I learned about Hebrew poetry while studying for a BA (Theology) degree in 2016 as one of my retirement projects. The key features of ancient Hebrew poetry were recognised and popularised by Bishop Robert Lowth in the 1750s. One of the discoveries associated with him was that each line was about an idea and the division of the line into parts reflected the doubling or even tripling of a description of the same idea. This feature is described as parallelism. It is shown in the use of different words to express the same idea, though occasionally, there may be a contrast or development. Here, in Psalm 58:1, is an example of how it is expressed,

| Do you rulers indeed speak justly? Do you judge uprightly among men? | Unjust human rulers |

This is a single poetic line that is set out as in the NIV Bible with the second part indented. On the right is my understanding of the idea that features in the line. I use this style throughout my analysis of the psalms. The alternative use of a contrast or development of the idea is unusual in individual lines but is more common at other levels of parallelism.

Another feature of the poetic structure of individual lines, but one that does not translate into English is illustrated in Psalm 58:6,

| Break the teeth in their mouths, O God; tear out, O Yahweh, the fangs of the lions! | Demands that Yahweh wreak vengeance on his behalf |

Different words are used in the two parts but the idea expressed is the same – the parts are parallel. In Hebrew however, the word order is different so it reads,

The parallel parts are in reverse order. This is called a chiasmus (from the Greek for ‘crossing’). This construction is lost in translation as English grammar requires a different word order. However, though it is a common construction at this level, within a line, it does not add to the meaning of the psalm. It is interesting and we are impressed with the writer’s skill and cleverness but that is all. However, it is a pattern, like the parallels between the parts of a line, that also features in the overall construction of a psalm.

These fine details of Hebrew poetry are well known among Bible scholars, for much of the literature in the heyday of Hebrew poetic studies in the 19th and early 20th century concerned the detailed micro-construction of individual lines and words and that requires a thorough knowledge of the Hebrew language. Now, in the 21st century, of the eight modern(ish) Psalm commentaries/reference books I frequently consult only one[3] takes an interest in the poetic structure. However, this interest does not extend to the meaning and message of the psalm. Not surprisingly, therefore, little seems to have filtered through into sermons or pastoral biblical literature.

Poetic structure is an intrinsic contribution to the meaning of poetry and as parallelism, rather than rhythm and rhyme, is the key feature of Hebrew poetry it ought to translate largely intact. And if Scripture is ‘God-breathed’ (2 Timothy 3:16), as I believe, the poetic structure will be an essential a feature of the scriptural text as is grammar and the way words are used – for example, whether they are intended to be understood either literally or figuratively. And the point is, that this applies not only to the original Hebrew but also to translations into other languages. Amazingly, it looks as of the main features of the poetic structure will be discoverable without the need to understand Hebrew. That conclusion emboldened me to largely ignore the features of parallelism that required knowledge of Hebrew and concentrate on those that are evident in English translations.

By trail and error I worked out that the first step is to identify the idea expressed in a line. However, I soon realised that in some psalms lines were grouped and expressed a single idea. It seemed that this was the basic Hebrew poetic unit. I have adopted the poetic descriptive word ‘strophe’ to describe these. In its simplest form each strophe is a single line as in Psalm 100 while in Psalm 88 they are couplets. It can be more complicated. Psalm 147, for example, is a mixture of one, two and three line strophes. The second step is then to look for parallels between the strophes, experiment with different arrangements and see how that impacts what seems to be the theme of the psalm.

The first psalm I studied where this fell into place was Psalm 58. I am not sure now why I chose it but I was interested in lament psalms and this was a particularly horrific example. Perhaps I was hoping against hope I would find something positive that would explain why such a diatribe was included in Scripture. I decided to highlight the words that seemed to have parallels elsewhere and this is what I discovered:

| 1 Do you rulers indeed speak justly? Do you judge uprightly among men? | Unjust rulers |

| 2 No, in your heart you devise injustice, and your hands mete out violence on the earth. | Unjust violence |

| 3 Even from birth the wicked go astray; from the womb they are wayward and speak lies. | Wicked go astray |

| 4 Their venom is like the venom of a snake, like that of a cobra that has stopped its ears, 5 that will not heed the tune of the charmer, however skilful the enchanter may be. | Similes |

| 6 Break the teeth in their mouths, O God; tear out, O LORD, the fangs of the lions! | ?Chiasmus |

| 7 Let them vanish like water that flows away; when they draw the bow, let their arrows be blunted. 8 Like a slug melting away as it moves along, like a stillborn child, may they not see the sun. | Similes |

| 9 Before your pots can feel [the heat of] the thorns – whether they be green or dry – the wicked will be swept away. | Wicked swept away |

| 10 The righteous will be glad when they are avenged, when they bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked. | Righteous vengeance |

| 11 Then men will say, “Surely the righteous still are rewarded; surely there is a God who judges the earth.” | A just God |

There were definite parallels between the first three verses and the last three and verses 4 and 5 were metaphors as were verses 7 and 8. That left verse 6 at the centre of a chiasmus if one did actually exist! I looked for other ways lines could match without success so then spent some months intermittently examining the structure, seeking alternative layouts and examining other psalms too. I eventually decided that as far as I could tell the psalmist had structured Psalm 58 in a chiasmus as shown below.

When referring to the Hebrew structure of a psalm I ignore the verse numbers and instead use a letter/number combination for each strophe. Notice that D and D1 have two lines each but otherwise the lines are separate strophes. Although lines are the normal poetic unit in English and presumably in other languages too, in Hebrew the strophe is the basic poetical unit. It may have more than one line but always has only one idea.

| A | 1 Do you rulers indeed speak justly? Do you judge uprightly among men? | Unjust human rulers |

| B | 2 No, in your heart you devise injustice, and your hands mete out violence on the earth. | Injustice expressed violently |

| C | 3 Even from birth the wicked go astray; from the womb they are wayward and speak lies. | The wicked cannot be controlled |

| D | 4 Their venom is like the venom of a snake, like that of a cobra that has stopped its ears, 5 that will not heed the tune of the charmer, however skilful the enchanter may be. | They appear to be similar to an uncontrolled venomous snake |

| X | 6 Break the teeth in their mouths, O God; tear out, O LORD, the fangs of the lions! | Only Yahweh can wreak vengeance |

| D1 | 7 Let them vanish like water that flows away; when they draw the bow, let their arrows be blunted. 8 Like a slug melting away as it moves along, like a stillborn child, may they not see the sun. | In reality they are similar to natural features of life that have only a brief existence |

| C1 | 9 Before your pots can feel [the heat of] the thorns – whether they be green or dry – the wicked will be swept away. | But Yahweh can easily get rid of the wicked |

| B1 | 10 The righteous will be glad when they are avenged, when they bathe their feet in the blood of the wicked. | Justice/revenge can be expected |

| A1 | 11 Then men will say, “Surely the righteous still are rewarded; surely there is a God who judges the earth.” | Yahweh the just God |

This structure indicates that the psalm has three stanzas but these are based on the poetic structure so are different to the NIV’s stanzas based on subject matter. They each have their own theme:

Stanza 1 The uncontrolled power of ungodly leaders.

Stanza 2 Retribution demanded.

Stanza 3 Yahweh, the righteous judge has the greater power and authority.

Each stanza contributes to the overall theme of the psalm that Yahweh, the righteous and compassionate judge, should be in control. This poetic structure throws new light on the meaning of the psalm as there are undoubtedly some positive insights that soften what originally appeared to be an appalling, shameful and ungodly attitude. Still, however, the general impression is that the psalm is about meeting violence with even more ruthless violence.

According to my study notes, it was 2014 when I started to look at Psalm 58 and by 2017 I had done a basic analysis as above. I largely neglected it from then until 2022 as I needed a lot more background knowledge to be able to understand the metaphors and the customs and lifestyle that were essential components of the setting of the psalm and its writer’s style of expression. Even more importantly, I needed time to find out if what I had discovered had any relevance in other psalms.

During the years I was studying psalms I was also involved in a trauma healing ministry in which we used lament psalms to aid understanding of how believers behave when they suffer trauma during and following bad experiences. I was therefore able to see that the psalmist’s belligerence was an understandable reaction to his experiences. I came to recognise that Psalm 58 is NOT teaching how we should respond to injustice, nor is it teaching that we can expect Yahweh to cooperate with our ideas for vengeance. Rather, it is expressing the passion and hurt even godly people feel when they see or experience injustice, suffering or even milder forms of hurt. Lament psalms, such as Psalm 58, teach us that we should not ignore, devalue or suppress such emotions. However, they are only ONE aspect of a response to injustice. I explore this further in my notes on Psalm 58 and have found this insight helpful in assessing and understanding the other, and actually quite frequent, occasions when psalms are disturbing to read. Such passages trouble our Christian sensibilities but being in Scripture they are still God’s word so they have a message for us even in our generation and culture that is far removed from the psalmist’s situation.

I have now (December 2022) completed studies of 18 psalms sufficiently to be willing to make them available in ‘Psalm Insights’ for others to read, reflect on and hopefully to respond with comments and further developments and ideas that I have missed. I have another nine psalms that are in various stages of development.

I have been amazed at how many extra insights, understanding and spiritual truths have come to light in the course of my studies. May you find that too.

To learn more of how this psalm study developed go to Psalm 58 which is the ‘final’ version of the features introduced in this page.

In case you are wondering

The traditional study of Hebrew poetry has generated a range of technical terms to describe the various features but the meaning of some descriptors do vary according to who uses them. Here is a list that is as accurate as I can make it. In my notes I have avoided using specialised terminology as much as possible so here I have highlighted the few I do use and how I use them.

| Antithetical | Parallelism between the parts of a line in which the subsequent part(s) contrast to the idea expressed in the first part. |

| Bicolon | A poetic line consisting of two parts. Same as Dicolon. |

| Chiasm | Uncommon alternative spelling of chiasmus. |

| Chiasmus | Strophes are arranged in reverse order (from the Greek for ‘crossing’): A B C X C1 B1 A1. |

| Chiastic | Adverbial form of chiasmus. |

| Cola | Plural of colon. |

| Colon | A subdivision of a poetic line. |

| Couplet | A two line strophe sharing one idea. |

| Dicolic | Adjectival form of dicolon. |

| Dicolon | A poetic line consisting of two parts. Same as Bicolon. |

| Hemistich | A half-line of ‘verse’ (second meaning) that is occasionally used instead of colon. |

| Idea | The thought that is expressed in a poetic line or strophe. |

| Line | The basic unit of Hebrew poetry that consists of one or more parts with subsequent parts using different words that repeat, contrast or develop the idea expressed in the first part. |

| Part | I have opted out of using technical language as much as possible so the parts of a poetic line are just called ‘parts.’ |

| Parallelism | The key feature of Hebrew poetry in which ideas are matched with a related statement in a subsequent part of the line, or between lines or strophes. |

| Psalm | One of the collection of spiritual songs in the Book of Psalms. Equivalent to a chapter in other Bible books but the psalm divisions are original whereas chapter divisions were introduced later to help navigation. Songs, similar to, or even copies of psalms, occur in other parts of the Old Testament. They too may be referred to as psalms. |

| Quatrain | A four line strophe sharing one idea. |

| Strophe | A line or a group of lines that have a single idea that is the core building block of a psalm. Strophes are identified by a capital letter, A, B, C etc, in the left margin and any matching strophes are indicated with a number such as A1, A2. |

| Stanza | A grouped set of strophes within a psalm, separated from other strophes by a blank line. The idea expressed in each strophe is linked to a common theme which is an aspect of the theme of the psalm. Some authors use stanza as an alternative to strophe. I usually head each stanza with what I think is its theme. |

| Synonymous | Parallelism between the parts of a line or between strophes in which subsequent part(s) repeat the idea expressed in the first part. |

| Synthetic | Parallelism between the parts of a line or between strophes in which subsequent part(s) develop the idea expressed in the first part. |

| Tercet | A three line strophe sharing one idea. |

| Theme | The core message of a psalm or stanza. |

| Tricola | A poetic line consisting of three parts. |

| Tricolic | Adjectival form of tricolon. |

| Verse | The currently used arbitrary numbering of sections of text throughout the Bible that was established in the 16th century. They are only casually related to the Hebrew poetic structure of psalms but are retained as a convenient navigational aid. Confusingly, some scholars use verse as an alternative to strophe. |

| Verset | Occasionally used as an alternative to colon or line. |

Endnotes

[1] See a summary of theological scholarship about the poetic structure of the psalms in Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms, (Augsburg, MI: Augsburg Old Testament Studies, 1984), pp. 3-4 and Willem A. Vangemeren, ‘Psalms’ in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol 5 Revised Ed, ed. by Trumper Longman III & David E. Garland, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), pp. 27-29.

[2] The Holy Bible (NIV), Popular Cross Reference Edition, 1992, Translators’ Preface, p. x.

[3] Willem A. Vangemeren, ‘Psalms’ in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol 5 Revised Ed, ed. by Trumper Longman III & David E. Garland, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008).

Written: 1 February 2022

Published: 2 January 2023

Edited: 27 November 2023