Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light for my path. (Psalm 119:105)

Psalm 4 (NIV, 1984)

For the director of music. With stringed instruments. A psalm of David.

1 Answer me when I call to you,

O my righteous God.

Give me relief from my distress;

be merciful to me and hear my prayer.

2 How long, O men, will you turn my glory into shame?

How long will you love delusions and seek false gods? Selah

3 Know that the LORD has set apart the godly for himself;

the LORD will hear when I call to him.

4 In your anger do not sin;

when you are on your beds,

search your hearts and be silent. Selah

5 Offer right sacrifices

and trust in the LORD.

6 Many are asking, "Who can show us any good?"

Let the light of your face shine upon us, O LORD.

7 You have filled my heart with greater joy

than when their grain and new wine abound.

8 I will lie down and sleep in peace,

for you alone, O LORD,

make me dwell in safety.

Notes

1. It is not clear why NIV has 2-line stanzas except for verses 6-8 which has 3 lines; nor why verses 4 and 8 have tripartite lines whereas other verses have bipartite lines – yet all verses have a similar construction.

2. This represents the translators’ interpretation and it differs from other versions. For example:

Revised KJV has verse 2 in 3 parts and verses 4 and 8 in two parts.

GNB has tripartite verse 2 and 4 but not 8.

RSV has no tripartite lines.

3. I have not explored any further why there is this difference. But the key to understanding the line structure is to identify the idea promoted in each line or part-line[1] and that has been my guide in the following layout. As usual, I will adopt the poetic word ‘strophe’ for these lines.

4. This layout also uses Yahweh instead of ‘the LORD’ to better express how the psalmist addressed God.

Psalm 4 (simplified layout)

1 Answer me when I call to you,

O my righteous God.

Give me relief from my distress;

be merciful to me and hear my prayer.

2 How long, O men, will you turn my glory into shame?

How long will you love delusions and seek false gods? Selah

3 Know that Yahweh has set apart the godly for himself;

Yahweh will hear when I call to him.

4 In your anger do not sin;

when you are on your beds, search your hearts and be silent. Selah

5 Offer right sacrifices

and trust in Yahweh.

6 Many are asking, "Who can show us any good?"

Let the light of your face shine upon us, O Yahweh.

7 You have filled my heart with greater joy

than when their grain and new wine abound.

8 I will lie down and sleep in peace,

for you alone, O Yahweh, make me dwell in safety.

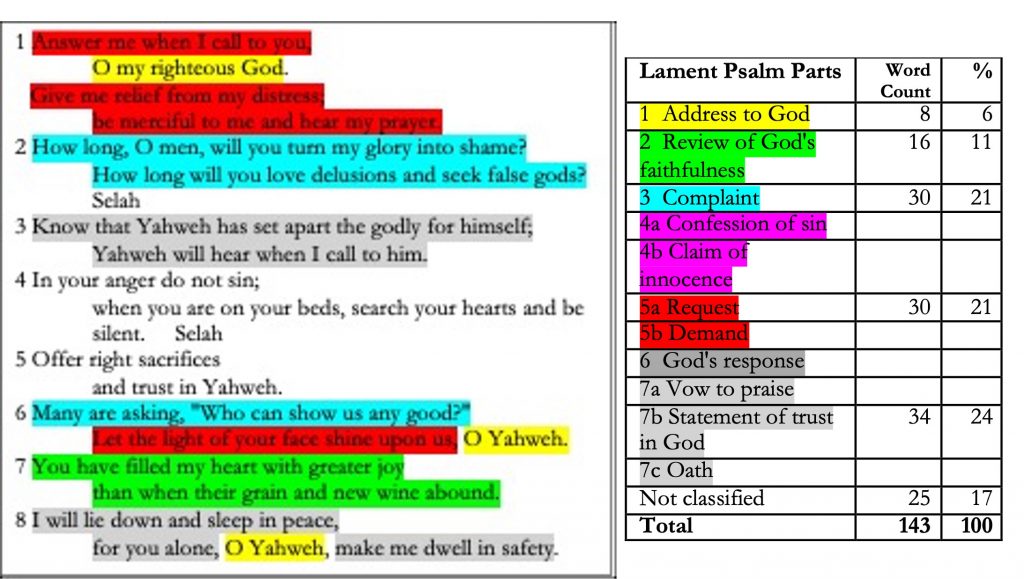

5. The analysis of Psalm 4 as a lament is shown in the image below. It is addressed to Yahweh, as usual, but the first complaint (verse 2) is addressed to ‘men’ who are antagonistic toward the psalmist as they seem to be planning to ‘turn my glory into shame,’ seemingly, by misinterpreting something that is not specified, perhaps an event or the psalmist’s behaviour. He claims they are guided by delusions inspired by the worship of false gods.

6. A second complaint (verse 6) is that ‘many’ of these men despair of obtaining positive and encouraging leadership for they complain, ‘who can show us any good?’ (6).

7. This lament is unusual for most biblical laments are addressed to Yahweh and are often complaints about Yahweh. That suggest the purpose of this lament is not the usual attempt to let Yahweh know how the writer feels about his disappointments and traumas. Instead, it seems to be intended to teach these ‘men’ the importance of being ‘godly’ (3) as being godly gives David the assurance of knowing that Yahweh ‘hears’ his cries for help with the implication that a response is ensured.

8. He therefore advises (4-5) how they too can experience Yahweh’s guidance. He seems to acknowledge that their anger is valid but advises that they need to be wary that this does not lead them into sin. He suggests, therefore, that they retire to their beds and reflect privately (‘be silent’) on their own role in the events they are concerned about.

9. Verse 5 continues with the advice that they should then make a point of responding to Yahweh in a way that reflects their cogitations. It is fair to assume that these men were fellow Israelites, so they would know the details recorded in Leviticus about the various sacrifices that were to be made that related to confessions of sin, thankfulness and peace. For this, see Leviticus 1:1-6:7 which describes these offerings from the offerer’s perspective. They would hopefully each recognise which was the ‘right’ sacrifice to make in their particular circumstances.

10. The principles underlying these offerings were and are more important than the details. So, whatever had gone wrong leading to this squabble (and perhaps, that is all it was) that had got out of hand, the priority was that each should ensure that they had a right relationship with Yahweh their God.

11. Humanly speaking we might have expected the psalmist to suggest that such quiet reflection would assist them in getting a better perspective on their concerns but, instead, he emphasises that their priority should be to respond to Yahweh and to act then in ‘trust’ in what Yahweh has revealed.

12. This illustrates the contrast that can exist between scriptural teaching and our common practices for even Bible believing, God-fearing followers of Jesus can unwittingly adopt secular belief systems, philosophies of life and traditional behavioural customs and cover them with a Christian veneer.[2]

13. Verses 4-5, that feature this advisory role are unusual for a lament psalm – the first time in studying 30 psalms that I have met it – as it does not feature as one of the recognised constituents of biblical laments.

14. However, it is impressively insightful and in keeping with biblical truth! There is no counselling, no detailed advice, nothing about, ‘if I were you …’ or, ‘when this happened to me …’ His message is simply, ‘trust in Yahweh,’ or as it is expressed elsewhere, such as in Hebrews 11, ‘live by faith;’ a major scriptural theme. It challenges us to put our own lives right with Yahweh and then trust him to guide in the practical details of life, especially in our relationships with others.

15. The psalmist encourages these men with a testimony of his own experience (7-8) which, he implies, was when he followed the advice he had given them. That resulted in such great ‘joy’ that he measures it by comparing it with how people feel when they have an abundant harvest.

16. Bear in mind that the psalmist was addressing a rural community of subsistence farmers. Everyone lived off the land or were dependant on those who did, so they needed, year on year, to grow enough crops to enable them to survive the agricultural off-season and hopefully, have some spare that they could share or sell on. More details of this situation are provided in Psalm 91 especially notes 48-52. The stress, worry, fear and hard work of the agricultural year culminated in harvest, so an abundant harvest was satisfying and immensely joyful. The metaphor would be instantly understandable to the palmist’s original audience and to much of today’s ‘third world’ population but is alien to those who live in the super-abundance of wealth and luxury in the Western world that provides all and even an over-provision to supply needs and wishes for food and materials for life in supermarkets and corner shops at virtually any and every time of the year.

17. But notice the psalmist refers to, ‘their grain and new wine,’ not ‘your.’ It seems he was no longer addressing these ‘men.’ That tiny change is a poetic shortcut whereby he includes all who welcomed an abundant harvest – that is, the whole nation. This teaching was not just for the men he had upset. Everybody was encouraged to trust in Yahweh.

18. The psalm concludes with the psalmist’s declaration that he now sleeps soundly (8). It seems he no longer needs to spend the night brooding or worrying.

19. Further insight into this psalm is obtained when the psalm is seen in the light of the psalm’s poetic structure that is based on the ideas promoted – this is described in the third column in the table below. The psalm is unusual as it has a double chiastic structure in which each strophe has a matching partner but also the strophes are in pairs and these paired stanzas are also arranged chiastically.

Psalm 4 (Hebrew poetic structure) –

A testimony of Yahweh’s help when believers fall out

| Stanza 1 | David requests help from Yahweh | |

| A | 1 Answer me when I call to you, O my righteous God. | Request addressed to Yahweh. |

| B | Give me relief from my distress; be merciful to me and hear my prayer. | Requests relief from distress. |

| Stanza 2 | Resolution of differences requires recognition of Yahweh’s assessment | |

| C | 2 How long, O men, will you turn my glory into shame? How long will you love delusions and seek false gods? Selah | Many are seeking help in wrong places. |

| D | 3 Know that Yahweh has set apart the godly for himself; Yahweh will hear when I call to him. | Life’s answers are found in Yahweh. |

| Stanza X | Resolution of differences requires a change of attitude | |

| X | 4 In your anger do not sin; when you are on your beds, search your hearts and be silent. Selah | Yahweh looks beyond behaviour and is concerned about attitude. |

| Stanza 2a | Resolution of differences requires us to live life Yahweh’s way | |

| D1 | 5 Offer right sacrifices and trust in Yahweh. | Right living and trusting in Yahweh is the way forward. |

| C1 | 6 Many are asking, “Who can show us any good?” Let the light of your face shine upon us, O Yahweh. | Yahweh’s guidance is the right way for everybody. |

| Stanza 1a | Yahweh supplies the help David requests | |

| B1 | 7 You have filled my heart with greater joy than when their grain and new wine abound. | Distress replaced with joy. |

| A1 | 8 I will lie down and sleep in peace, for you alone, O Yahweh, make me dwell in safety. | Yahweh answers by providing peace and safety. |

20. In stanza 1, strophe A, David requests personal help from Yahweh whom he addresses as the ‘righteous God,’ and in strophe B his request is for relief from distress.

21. In stanza 2, strophe C, he explains something about his distress. It seems he was misunderstood by ‘men’ that probably refers to disaffected citizens who looked to him for leadership. He claims they misunderstood as shameful, something that he found glorious, honourable and a blessing. He claims they were led astray by basing their opinions on an association with those who worshipped gods other than Yahweh.

22. He contrasts that with a bold claim in strophe D that ‘the godly,’ of which he was one, who were devoted to Yahweh, had the assurance that Yahweh heard their prayers.

23. In these succinct poetic strophes the psalmist is teaching a basic biblical truth about putting our lives right before Yahweh as a prerequisite for resolving personal differences. We should ask Yahweh for help. This is a recurring theme throughout Scripture:

Call upon me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you will honour me (Psalm 50:15).

Until now you have not asked for anything in my name. Ask and you will receive, and your joy will be complete (John 16:15).

Let us then approach the throne of grace with confidence, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help us in our time of need (Hebrews 4:16).

24. We are not to depend on our own attempts to please him (‘Surely, God will be pleased with this’) or attempt to bully him (‘I deserve this’) or to bargain with him (‘if you do this, I will do that’), for all have the aim to persuade Yahweh to agree to our demands. Instead, David acknowledges that Yahweh has ‘set apart the godly for himself.’ However, it is all too easy to take that phrase as an exclusive statement but, in actuality, that contradicts Yahweh’s inclusive welcome to all who call on him:

Yahweh is near to all who call on him, to all who call on him in truth (Psalm 145:18).

25. The point being made is about Yahweh’s commitment to those who turn to him. The psalmist will come to how we should respond in due course.

26. Stanza X, in the centre of the psalm, is not paired so it stands out. This is a common poetic technique to emphasis the main teaching point of the psalm. This is that resolution of their differences depended on their attitude of heart. This was more significant than having the better arguments or stronger army.

27. David accepts these men were angry. He has no problem with that but he is concerned that their anger does not lead to sin so advises they take to their beds – but not to sleep!

28. Beds in ancient times, and also, to my knowledge, in rural Africa today and probably in many other parts of the less-developed world, were not just for sleeping at night. They could well be the only seating in the home.

29. Taking to their beds to ‘search your hearts and be silent’ suggests they would be fully awake, but on their own, reflecting on their personal behaviour, thoughts and attitude.

30. The first four stanzas are paired with the last four in reverse order.

31. Stanza 2a, strophe D1 develops strophe D by describing how the godly express their faith by their behaviour. It was by living a life characterised by ‘trust in Yahweh,’ exactly as it us for us. In his day, though, this commitment was expressed by the requirement to ‘offer right sacrifices’ according to the worship schedule that Yahweh had set for them in the Levitical law (Leviticus 1-7). Such offerings were at the choice and decision of the offerer and were not part of the routine daily worship nor the national festival offerings (Leviticus 16, 23).

32. We are not left to our own devices in working out how we can live ‘trusting in Yahweh’ for Yahweh himself is waiting to guide us in the right way. In contrast to the men in strophe C who seek help from other gods, and are now asking in the parallel strophe C1, ‘who can show us any good,’ that is, the best way forward, David confidently turns to Yahweh and requests, ‘Let the light of your face shine upon us, O Yahweh.’

33. These words are to be understood metaphorically so the sentence strikes me as being related to a bright day with the sun shining clearly and comfortably but not blazing and burning. ‘Light’ is about being able to see the way forward. Reference to ‘face’ suggests Yahweh is identifiable and is personal. ‘Shine’ expresses comfort, clarity and warmth. ‘Us’ indicates this is a shared experience. By using ‘us,’ David thereby aligns himself with those whom he is advising – and that is another reason for the suggestion that this is not about correcting sin or standing up to ‘enemies’ but is about resolving a serious difference of opinion with ‘opponents’ who otherwise would be colleagues and fellow citizens.

34. As for them so for us – when there are serious differences of opinion and a risk of falling out. Rather than take sides and prepare for battle – them versus us – the godly way is for all who are involved to privately seek Yahweh’s light, guidance, direction and wisdom. It is stunningly true that Yahweh wants such a relationship with us and it is not just for us personally, it is for everyone.

35. The psalm does not go into details about exactly how they should behave as this was already covered in the Mosaic Law. This includes the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17) and the injunction to love our neighbour as we love ourselves (Leviticus 19:18). The psalmist only needed to remind his people of the principle.

36. Finally in stanza 1a, David provides his personal testimony of his experiences of Yahweh’s help that he asked for in stanza 1.

37. Instead of the distress he refers to in strophe B, his heart is now filled with great joy (strophe B1). As a measure of his joy, he claims it exceeds the joy experienced at a good harvest when ‘grain and new wine abound.’ In a largely rural community of subsistence farmers, that metaphor would be instantly understood and appreciated. Everyone lived day to day, year on year, so the only way to ensure the community’s survival was a good harvest that would see them through the year until the next harvest.[3] Deuteronomy 16:13-15 describes Yahweh’s expectation for the joyful celebrations at the end of harvest at the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths that is alternatively referred to as the Feast of Ingathering.

38. We do not know any details of what was causing David’s distress (strophe B), nor do we know how it was resolved but the main teaching point is about the change in David’s perspective. Knowing that Yahweh is in control and is watching out for him, David can rest in peace. He sleeps soundly and has confidence that Yahweh is alert and watchful, so he is kept safe (strophe A1).

39. That is David’s testimony and he leaves it at that, but the message of the psalm is that his experience can be had by others too – even, and perhaps especially – by those who were causing David to be distressed. There are no details to help us work out who they were or what had gone wrong between them but neither is there any suggestion that this was a serious or sinful issue.

40. I think this assessment is still true even though David believed that his opponents were deluded by their interest in the worship of false gods (strophe C), whereas to us in our day, we are likely to equate the worship of false gods with what we know about those who follow religions other than Christianity. That means it is possible to miss the significance of these few words.

41. Bear in mind that everyone was religious in David’s day so his complaint that his opponents, ‘love delusions and seek false gods’ (strophe C), does not necessarily mean that they were actively turning away from the worship of Yahweh and were changing their allegiance to Baal or another god that was worshipped by neighbouring tribes. They were just ‘seeking’ and that implies they were not yet committed. Inevitably though, there would be a risk that they would progress on a path that could lead to such apostacy. The statement could well just mean that were adopting patterns of behaviour that related to the style of life, attitudes and belief systems of neighbouring peoples that did worship false gods.

42. There is a parallel here with how we may behave when we are in a similar situation such as when we are faced with a serious difference of opinion with fellow believers. It is so easy to be offended, view what happened only from our own perspective and withdraw into the ‘safety’ of a closed community of those who think and act like we do. This develops the comments made in notes 11-14.

43. But that is not following Yahweh’s way as expressed in, ‘love your neighbour as yourself’ (Leviticus 19:18). It is not about an attitude that, ‘should be the same as that of Jesus Christ,’ as developed in Philippians 2:5-11. It is not following the command to, ‘Trust in Yahweh with all you heart and lean not on you own understanding’ (Proverbs 3:5).

44. This is following ‘the wisdom of the world’ that Paul berates the church in Corinth for doing (1 Corinthians 3 onwards) and that is the equivalent of Psalm 4’s complaint that the people, ‘love delusions and seek false gods.’

45. It seems that in our world Christian families and communities can be torn apart seemingly as easily as any human organisation when there are serious differences of opinion. Friendships can be broken, siblings stop meeting or talking to each other, others are expected to take sides and believers may move to another church.

46. This is such a common problem we have counsellors and mediators both in the secular and Christian worlds. We can be helped to see our opponents’ point of view, we can learn to bargain and compromise. However, we may be left with doubts and fear about possible future recurrences. For our own peace of mind and due to a loss of self-confidence and even doubt of the importance of trusting in Yahweh’s guidance and help, we may still withdraw. For some this can be the start of a slippery slope that leads to a loss of faith and even a developing antagonism to all that the Christian Faith stands for.

47. This behaviour is, I think, the modern-day equivalent of ‘seeking false gods’ for this way of responding to relationship problems is NOT responding in the godly way that David advises but is using secular techniques that are based on a secular philosophy of life. There is nothing wrong with the techniques themselves. It is the underlying philosophy that is the problem, coupled with an overdependence on such techniques and the neglect of spiritual considerations.

48. Rather than condemning, arguing with or contradicting his opponents or insisting on his right as king to overrule them, David invites his opponents to wait on Yahweh in quietness, to reflect on their own attitude and behaviour as a double check that their right to express their opinion does not lead them to go too far and commit sin.

49. It seems that this was the approach that David had adopted. His testimony was that he had a peaceful mind, so could sleep soundly and live securely.

50. This is a powerful and needed message for us today.

Endnotes

[1] For further information about the structure of Hebrew poetry see Introduction to Hebrew Poetry.

[2] For example, Christopher Wright comments, ‘The order of the commandments thus gives some insight into Israel’s hierarchy of values. Roughly speaking, the order was God, family, life, sex, property. It is sobering, looking at that order, that in modern society (in its debased Western form at least) we have almost exactly reversed that order of values. Money and sex matter a lot more than human life, the family is scorned in theory and practice, and God is the last thing in most people’s thinking, let alone priorities.’ Christopher J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, (Inter-Varsity Press: Nottingham, 2004), p. 307.

[3] J. L. Kelso and F. N. Hepper, ‘Agriculture’ in J. D. Douglas and others (Eds.), The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1980), pp. 20-22.

Written: 3 July 2022

Published: 12 January 2026