Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light for my path. (Psalm 119:105)

Psalm 3 (NIV)

A psalm of David. When he fled from his son Absalom.

1 O LORD, how many are my foes!

How many rise up against me!

2 Many are saying of me,

"God will not deliver him." Selah

3 But you are a shield around me, O LORD;

you bestow glory on me and lift up my head.

4 To the LORD I cry aloud,

and he answers me from his holy hill. Selah

5 I lie down and sleep;

I wake again, because the LORD sustains me.

6 I will not fear the tens of thousands

drawn up against me on every side.

7 Arise, O LORD!

Deliver me, O my God!

Strike all my enemies on the jaw;

break the teeth of the wicked.

8 From the LORD comes deliverance.

May your blessing be on your people. Selah

Notes

1. My initial impression on reading Psalm 3 was that it was about David’s experience of ‘Trusting Yahweh in Adversity’ but later, I came to believe that it was more particularly an ‘Appeal for Reconciliation’ from the writer, King David, to the citizens who had rebelled against his leadership. My concluding impression, however, is that Psalm 3 reflects a particular stage in the process of the ‘Rehabilitation of a Fallen Leader.’ All three themes are complementary; they are not contradictory. These themes are based on a study of the poetic structure of the psalm and the history and culture in which it is based. Interestingly, this study too, brings into spiritual perspective some of the sordid and embarrassing stories recorded in Scripture.

2. Psalm 3 illustrates an experience a fallen leader goes through on the journey of recovery back into leadership that relates to the reconciliation that needs to take place between the leader and those who have been hurt, damaged and distressed by his attitude and behaviour. This topic needs to be addressed with care and caution as it has very serious implications for the spiritual well-being of those who have suffered at the hands of a fallen leader. Nevertheless, it is possible that such sufferers will appreciate and be helped by considering what Psalm 3 has to say, so hopefully, will be able to then move further along their own journey of recovery and spiritual healing.

3. This may well seem far-fetched at first sight but journey with me to discover how the Psalm develops and see if you find this to be a valid observation.

4. King David, the psalmist, writes Psalm 3 as a lament as he is in serious trouble surrounded by ‘tens of thousands’(6) of enemies but he still writes personally (not on behalf of the people) so this supports the idea that he is writing about personal enemies such as occurred at the instigation of his son, Absalom, who attracted a huge number of disaffected citizens to his rebellion (2 Samuel 15:10-13). That suggests that it is those rebellious citizens who are referred to in, ‘Many are saying of me, “God will not deliver him”’(2). They had become his ‘foes’ (1) and ‘enemies’ (7). It is only in the last verse that he mentions ‘your people’ who could be those who remained faithful to David as Yahweh’s anointed king. However, ‘your people’ generally refers to the nation as a whole[1] so could, even here, this be true, so the rebels are also included?

5. David does not share the rebels’ opinion that God had forsaken him. In the circumstances, he seems to be remarkably relaxed and confident in Yahweh (3). He prays loudly and publicly (4) and such is his confidence, he sleeps soundly and wakes refreshed (5).

6. Victory, however, is not yet complete so he prays for deliverance and expects this to come in Yahweh’s violent treatment of his enemies (7). However, he does not pray for their annihilation, as we might expect from studying other psalms, but for them to be wounded so they suffer serious and permanent injuries that were unlikely to be lethal. Such wounding, a powerful punch to the jaw, is more likely to occur in personal combat rather than in a pitched battle where ‘tens of thousands’ are involved, so it is a curious choice of phrase; and he expects Yahweh to deliver this blow! This is so bizarre there must be something significant about these specific details. We come to that in note 17.

7. The title says that this psalm refers to Absalom’s rebellion (2 Samuel 15) though Absalom is not referenced nor are there any details to make that connection (apart from the observations in note 4).

8. In Jewish Bibles the title is counted as verse 1 but there is no poetical reason or internal clue to suggest the title is any more than a later but still very ancient interpretive addition. See Psalm 13 (notes 29-33) and Psalm 58 (note 63) for further comments about psalm titles.

9. Having said that, however, the psalm’s contents can be seen to relate to events that followed Absalom’s rebellion rather than the rebellion itself.

10. By the time of the rebellion, David had lost a measure of the aura associated with being a national hero and Yahweh’s chosen leader and king. This seems to have developed after it became public knowledge that David had committed adultery with Bathsheba (or was it rape?) and had commissioned the murder of Uriah, her husband and his friend and fellow warrior (2 Samuel 11). That appalling behaviour occurred probably 10-12 years before Absalom’s rebellion. During those intervening years, David’s authority over family members disintegrated as some behaved as badly as David had but were not disciplined (2 Samuel 13-14). That suggests that David had lost his self-confidence as Yahweh’s anointed leader and had withdrawn from taking responsibility that such a role required. No one from his team of leaders and advisers seems to have called him to account so such a leadership vacuum prepared the ground for Absalom’s rebellion and campaign to usurp David’s role as king (2 Samuel 15). So many joined Absalom’s rebellion, including one of David’s top army officers (Amasa, 2 Samuel 17:25) and a senior adviser (Ahithophel, 2 Samuel 15:12-17:23) that David fled Jerusalem. And even after Absalom was defeated and killed the rebellion continued for a while as the people hesitated in recalling David to the throne (2 Samuel 19: 8b-14). When that did eventually happen there was a second rebellion led by Sheba (2 Samuel 19:41-20:22). Psalm 3, therefore, seems most likely to relate to the situation some time after David’s grief over Absalom’s death had abated and probably to the period following Sheba’s death.

11. Psalm 3 is a lament that is addressed to Yahweh, the God David worshipped and served, who had given this name to be used by his people. It is a name that reflects God’s nature (Exodus 3:14) as the ‘Always I Am.’ This is the primary way God is addressed throughout the OT. Only later, maybe 400-200 BC, was it considered to be too holy to use, so by the time Jesus came, it was the custom to use the title Adonnay (Lord) instead of Yahweh. The early church continued this practice but during the Reformation it seems to have been Luther who introduced the custom to distinguish Lord meaning Yahweh, by spelling it in capitals: LORD.[2] That custom has been adopted since then by most German and English protestant translations. This explanation is rarely mentioned so it is not surprising that most Bible readers will not be aware of the significance of knowing and being encouraged, even commanded, to use Yahweh’s personal name.

12. To seek to understand the OT as the writers intended I will return to the original use of Yahweh when referring to our God.

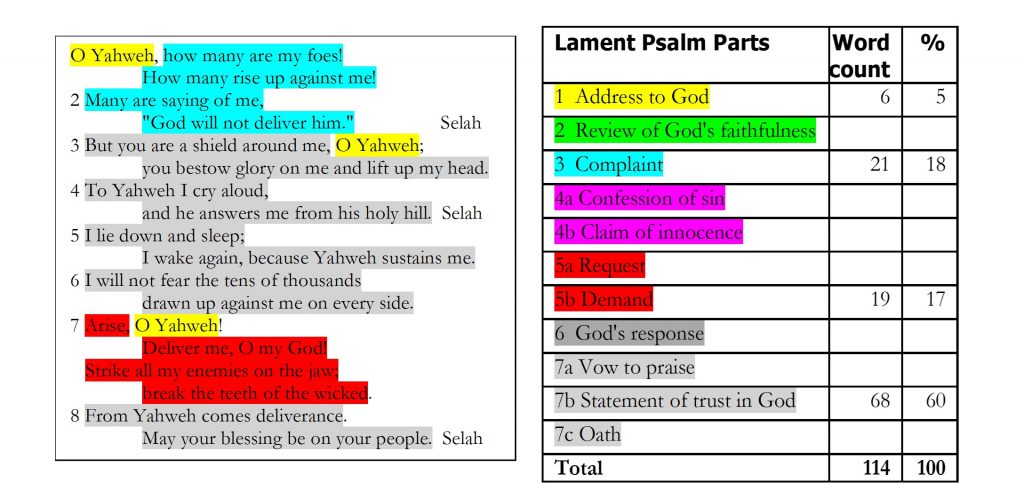

13. The lament is addressed to Yahweh so it has a complaint, the key characteristic of a lament. David then expresses his request in the form of a demand and an instruction about how he expected Yahweh to answer. Most of the psalm, 60%, however, is a reflection on Yahweh’s goodness, guidance and care so it softens the aggressive demands he makes.

14. The Hebrew poetic structure that is discernible from the matching of ideas between parallel strophes suggests there are two stanzas. The first expresses David’s personal confidence in Yahweh. It is arranged chiastically with the key point about Yahweh being the source of that confidence in the centre. The second stanza is a one line insistence that such confidence can be shared by all. Hence, my initial sense of the theme of the psalm was, ‘trusting Yahweh in adversity’ that was expressed personally and encouraged communally.

15. However, there could be a deeper meaning in the psalm that is discernible when the Hebrew poetic structure is explored and the psalm is seen in the light of the rebellion that it appears to refer to. That will explain the alternative title, ‘an appeal for reconciliation.’

Psalm 3

Trusting Yahweh in Adversity/An appeal for Reconciliation

| Stanza 1 | Personal confidence in Yahweh/The need for an appeal for reconciliation | |

| A | 1 O Yahweh, how many are my foes! How many rise up against me! | Too many enemies. |

| B | 2 Many are saying of me, “God will not deliver him.” Selah | Deliverance is thought to be unachievable. |

| C | 3 But you are a shield around me, O Yahweh; you bestow glory on me and lift up my head. | Confidence for deliverance. |

| X | 4 To Yahweh I cry aloud, and he answers me from his holy hill. Selah | Yahweh responds to David’s plea. |

| X1 | 5 I lie down and sleep; I wake again, because Yahweh sustains me. | David’s evidence of Yahweh’s response. |

| C1 | 6 I will not fear the tens of thousands drawn up against me on every side. | Confidence for deliverance. |

| B1 | 7 Arise, O Yahweh! Deliver me, O my God! | David believes that deliverance is possible when Yahweh is involved. |

| A1 | Strike all my enemies on the jaw; break the teeth of the wicked. | Many enemies can be overcome. |

| Stanza 2 | The national community can also have such confidence in Yahweh/Reconciliation is achievable with Yahweh’s inspiration and guidance | |

| 8 From Yahweh comes deliverance. Your blessing is on your people. Selah | Yahweh, is the source of deliverance for all Yahweh’s people. |

16. Stanza 1 consists of eight one-line strophes that are arranged chiastically.

17. In strophe A David complains about his many enemies but it is more of a statement of fact than a complaint which, in other psalms, is often expressed bitterly and angrily. It is matched in strophe A1 by his request that Yahweh punish those enemies by punching them in the jaw severely enough to break their teeth. A punch to the jaw is the sort of wounding that would happen in one to one combat, in, for example, an argument that got out of hand and led to fisticuffs, or in fighter training schools. It is a mannish and human type of assault and not a punishment such as floods or plague that is more readily associated with Yahweh’s retribution for wrongdoing. The request for retaliation toward his enemies is often for their destruction or even the annihilation of the whole community (Psalm 79 notes 30-33 and Psalm 21 notes 23, 29-37) so the comparative mildness and nature of the ‘punishment’ suggests it was for people who had gone astray and there was hope for restoration of a relationship with them. Furthermore, this ‘punishment’ would be more understandable if it related to an individual or a few people so it seems bizarre when the enemies number many thousands.

18. Notice too, the hint of humour in the image that this figure of speech creates in the reader’s mind. It is as if David invites Yahweh to participate in a boxing match! That is countercultural and counterintuitive for in a boxing match there is a risk of sustaining an injury as well as inflicting one and it is preposterous to even think of Yahweh participating in a brawl. The reason for these oddities is explored in note 61.

19. David quotes his enemies, who in this context are his disaffected citizens, in strophe B as being convinced that God will not deliver him. That is contrasted in the matching strophe B1 with his own confident call to Yahweh to deliver him.

20. That confidence is expanded in strophe C where he compares Yahweh to a megan shield – the small shield a warrior carried. His deliverance is emphasised in the ‘glory’ he would gain. His head would be ‘lifted up,’ in acceptance and approval, not bowed in rejection and defeat. His confidence in Yahweh’s deliverance is so strong he declares in the parallel strophe C1 that he therefore will not be afraid even when faced with countless numbers of enemies, even ‘tens of thousands;’ which is probably hyperbole so does not suggest there was a headcount.

21. I think it is significant that there is no hint of the boasting or self-righteousness that were features of an earlier stage in David’s kingship (Psalm 21). The emphasis is on Yahweh. This humility expresses what appears to be David’s new-found awareness and appreciation that he has been returned to be King only because of Yahweh’s mercy and grace. This is explored further in note 61.

22. At the crux of the psalm are the paired strophes X and X1 in which he declares the source of his confidence to be Yahweh himself, who responds to his cry from his ‘holy hill,’ a reference to the Tabernacle as a metaphor for heaven as Yahweh’s dwelling place (see Psalm 15). Because of this, his confidence is so sure, he can go to bed and sleep well, rather than lie awake worrying, and he wakes refreshed and energised, ready for the day.

23. Stanza 1 powerfully expresses David’s testimony of his recovery from his own traumatic experiences of facing seemingly overwhelming opposition. And that testimony focusses on Yahweh’s intervention (strophe X).

24. That leads into stanza 2, which is a single strophe, that builds on the evidence of David’s personal experiences and enables him to encourage Yahweh’s ‘people’ to share his confidence. Initially I thought that this referred to those who remained faithful to David against the rebels and, secondarily, to readers and singers of this psalm, including us, to follow his example and trust in Yahweh for, ‘from Yahweh comes deliverance.’ However, in the context of the usual use of this phrase it is more likely that David was referring to the nation as a whole that would include the rebellious citizens (see note 4). I see stanza 2, therefore, as a plea for reconciliation with the rebels and anyone else who was disaffected or troubled by the part David himself had played in causing these traumas.

25. Please remember that Israelites did not earn the right to be Yahweh’s nation by living righteously or by obeying the Law, rather they were expected to live righteously and obey the Law as an expression of their status as Yahweh’s people. The rebels were still Yahweh’s people even though they were rebels. The same principal applies to followers of Jesus who are Yahweh’s people in our day, for Scripture declares that we cannot lose our salvation however far we wander away from our Saviour. When we fall away in our faith, as we will, Scripture calls for confession:

If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness (1 John 1:9),

for Yahweh has an open heart and longs for his wandering sheep to return to his fold,

The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. He is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance (2 Peter 3:9).

26. There has only ever been one way to obtain God’s favour and to be added into his family and counted as his ‘people’ (8) and that is by faith. This is expressed in Hebrews 11: 6, which refers to all humanity:

… without faith it is impossible to please God, because anyone who comes to him must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who earnestly seek him.

Then in verses 39-40, that refers specifically to OT believers:

These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect.

27. And faith, of course, needs to be understood in its classical definition of being, ‘belief in action,’ that is, belief that has weighed up the evidence and then has taken action. Nowadays, there is a more commonly used understanding that faith means taking action for which there is no logical basis. This topic is explored further in Psalm 11, notes 18-19.

28. NIV and some other translations spoil the impact of the first part of the strophe, ‘From Yahweh comes deliverance,’ by then ending with a prayer request, ‘May your blessing be on your people’ even though the original Hebrew seems to be a statement of fact as is expressed in the following translations:

… on your people is your blessing (Interlinear Bible)

Your blessing clothes your people! (Message)

What joys he gives to all his people. (TLB)

… thy blessing is upon thy people. (KJV, Darby and Douay-Rheims)

you … bless your people. (CEV).

29. If it is a statement of fact surely there is no need to keep asking as in:

… request may he bless his people. (GNT)

… may your blessing be on your people! (NIV and NRSV)

May Your blessing be upon Your people. (AMP)

Thy blessing be upon thy people. (ASV)

Thy blessing be on thy people. (Cohen).

30. To my mind, using ‘may’ or the passive voice suggests there could be some doubt about whether Yahweh is willing or able to act for all Yahweh’s people as he has done for David. I have therefore adopted what I think is David’s statement of fact in my version above.

31. The title of Psalm 3 seems to suggest that the psalm represents David’s state of mind during the turmoil of the people’s rejection of his status as king in favour of his son Absalom, so it is encouraging to read about his sense of peace, comfort and confidence. However, this does not match the narrative of events when David escaped into exile as he seemed to believe there was a strong possibility that his time as king was coming to a violent end (2 Samuel 15:13-14). When his army eventually went to fight the rebels he was absorbed in his grief that he expressed in his concern for the welfare of Absalom, his rebellious son (2 Samuel 18:5) to the exclusion of everything and everyone else (2 Samuel 18:32-19:4). There is nothing in these narrative passages to suggest David was experiencing the comfort that trust in Yahweh gave him as it is expressed in Psalm 3.

32. It was only after his army commander, Joab, spoke sternly to him (2 Samuel 19:5-7) that David began to change. He began to think about the future. He started planning a strategy to regain his kingly status (2 Samuel 19:11-15), and acted decisively and pragmatically in dealing with individual rebels such as Amasa (2 Samuel 19:13, 20:4-10) and Shimei (2 Samuel 19:16-23, 1 Kings 2:8-9). He treated Mephibosheth graciously (2 Samuel 19:24-30) and seems to acknowledge he had made a mistake in too readily accepting Ziba’s account of his failure to join him in his exile (2 Samuel 16:1-4). The text gives no sense of the timing involved but this would not be an instantaneous transformation. From what we know about how people respond to grief, especially in the complicated situation that David was in, this would have taken many months or even years. I think it likely, therefore, that Psalm 3 relates to events that occurred some time after Absalom’s rebellion. It probably reflects David’s response to the rebels after Sheba’s short-lived revolt ended (2 Samuel 19:41-20:22). David was then stronger emotionally and spiritually and was progressing well on his personal journey of grief toward recovery and healing from the trauma associated with Absalom’s rebellion and the nation being torn in two, as well as from the long-term self-inflicted traumas related to the family repercussions that followed on from his appallingly sinful behaviour toward Bathsheba and Uriah.

33. This was now the time, humanly-speaking, when David needed to take action to reestablish himself as the nation’s rightful king in the minds of both citizens who had remained true to Yahweh and faithful to David and citizens who had been caught up in the rebellion and may have actively participated in it. But how could he know he was Yahweh’s choice? Note 31 suggests he had doubts about this. Something, however, did happen to give him the confidence that is expressed in Psalm 3. We will come to that in note 69 but for now sense the uncertainty that pervaded the nation, including David, throughout this period.

34. I propose that Psalm 3 is a worship song that expresses David’s faith and sense of Yahweh’s blessing that he wanted the whole nation to experience for themselves. However, it also had a message for the whole nation but especially the rebels, about moving toward reconciliation between all the factions, on both sides, who had been involved or affected by the rebellion.

35. And that appeal was built on the assurance that David had received of Yahweh’s blessing and approval that was undeserved but expressed Yahweh’s mercy and grace.

36. Bear in mind that the narrative of events in 2 Samuel that relate to the setting of this psalm is not complete – and that is a feature throughout Scripture, for Scripture is not written as a chronological record of events that invites our understanding and even approval – and human nature being what it is, will undoubtedly inspire criticism! Instead, it reveals what Yahweh wants us to know so we learn of him and of his ways. For example, the story of Sheba’s short lived rebellion ends abruptly with his death so, ‘his men dispersed from the city, each returning to his home’ (2 Samuel 20:22). ‘His men’ refers to ‘all the men of Israel [who] deserted David to follow Sheba’ (2 Samuel 20:2). That would have been a significant number – probably many thousands – but unlikely to be the ‘the tens of thousands’ of the original rebellion.

37. Scripture does not tell us what happened to them. Did they continue as disaffected rebels looking for another leader? Did they live in fear of reprisals? Did they admit their errors and reaffirm their allegiance to King David? And if so, was that capitulation done willingly or did they feel it was forced on them? It is possible that all these varied responses were represented among the thousands of rebels.

38. These are fair questions to ask but we are left only with hints and hopes for Scripture is not written to satisfy our curiosity but to challenge our own faith and commitment. The God of the Bible is still God today and we read in the Psalms something about David’s spiritual journey that included references to his worship and his hopes and fears.

39. Although the narrative in 2 Samuel does not explain the details, it looks as if Psalm 3 was written at this time as a worship song (yes, laments are worship songs – see ‘biblical lamenting’ in Lamenting) that encouraged trust in Yahweh and also had a message for the nation. It was addressed to everyone but especially to the rebels, inviting them to be reconciled with King David and join together before Yahweh as his people. And this reconciliation was not between equals but between citizens and their king who pointed out the evidence that showed he had Yahweh’s favour (strophes X-X1). David wanted his people to accept his role as King wholeheartedly with Yahweh acknowledged to be their God (stanza 2).

40. We can assume that the people would know Psalm 51 in which David confesses unspecified sin that seems likely to relate to his adultery with Bathsheba and the murder of her husband Uriah and we can safely presume that was written after Nathan’s visit that is recorded in 2 Samuel 12:1-14.

41. That psalm is a powerful affirmation of Yahweh’s mercy and forgiveness that encourages us all to know that no sin is beyond Yahweh’s capacity and willingness to forgive:

… God our Saviour, who wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth (1 Timothy 2:3b-4).

… all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus (Romans 3:23-24).

And see also Hosea 11:1-11.

42. David’s confession of guilt was admitted publicly so we can expect Psalm 51 became a model for others to use even in David’s time as much as in ours.

43. However, this Psalm carried other messages that were unpleasant and shocking. They would perhaps be sensed and felt rather than intellectually understood so may not have been discussed at all widely. One such message was that the nation’s leader and spiritual guide was as vulnerable to moral failure as anyone else. That implied David could not be trusted.

44. We can well imagine the questions that would come into many minds:

Who is this man who has behaved so evilly and caused so much trouble to our nation?

What right has he to become king again?

Will we ever be able to trust him?

After the way he has acted how can he claim to have Yahweh’s blessing, guidance and help?

And what does all this say about Yahweh?

Yahweh had destroyed those who openly rebelled against him (they would be aware of stories that we too know about such as, after the people worshipped the golden calf while Moses was on Mount Sinai (Exodus 32:25-35) and when Achan took plunder from Ai (Joshua 7:19-26). Yet David’s restoration as king seems to suggest that Yahweh has his ‘special favourites’ who are not held fully to account when they go very seriously astray. That does not seem fair – neither to them nor to us.

45. If David, with his many wives and concubines could so casually take Bathsheba, another man’s wife, was any wife or daughter safe from him? No longer would it be an honour to have David visit a home or for a family member to be invited to visit or join the royal household.

46. If David had Uriah, his friend and fellow soldier-commander, killed so casually was anyone safe? ‘Fear the King,’ was the message that would be heard!

47. And if David behaved like that would it encourage other community and military leaders to behave similarly? ‘Do not trust anyone in power,’ was another message!

48. Humanly speaking there can be no way back. A leader who failed so badly is finished – they need to withdraw from public life. Protests about redemption and restoration are living a lie.

49. But that is not the situation that Psalm 3 relates to. David is back in control, seemingly with Yahweh’s blessing. That appears to be morally dubious and insulting to those who had suffered because of the leader’s transgressions. And even if David had truly repented and would never behave in such a way again how could anyone know for sure, and trust him again?

50. This illustrates the dilemma the church faces today, for Christion leaders do sometimes behave immorally and abuse others using their power and status to serve their own ends. That brings disrepute to the name of Yahweh our God. And those leaders may well have been used very powerfully by God and may appear to continue to be gifted by the Holy Spirit in many ways that the church desperately needs. So, would sidelining or ‘retiring’ them be an expression of the church’s vindictiveness and evidence of lack of grace and mercy that is at the heart of the gospel? We might wonder if leaders who seriously and publicly sin are a ‘special case’ who are to be treated differently to other believers.

51. Resolving these issues is as crucial as forgiveness if there is to be any possibility of reconciliation and being able once again to trust a leader who has bitterly failed to lead God’s people in a godly way.

52. Psalm 3 provides some insight and ideas about how this dilemma can be approached taking the variety of contrary interests into consideration. This gives rise to my third theme that complements rather than replaces the first two: The Rehabilitation of a Fallen Leader.

53. If we bear in mind the actual situation in which it is set we can learn something about how Yahweh is still at work in the process of reconciliation and communal healing after a spiritual leader has fallen.

54. However, the focus in this biblical model of rehabilitation is not on the fallen leader. It is not about their sin and shortcomings. It is not about the people who have been damaged and hurt by their actions. Nor is it about retribution or compensation and definitely not about rehabilitation! Instead, the focus is on Yahweh.

55. Everybody needs to reconnect with Yahweh, they need to reattune their lives with Yahweh and learn again to live under his guidance and for his honour and glory that will be expressed in their commitment to each other, as exemplified in Psalm 15.

56. Indubitably, in these circumstances it would be morally and spiritually wrong for David to demand the allegiance of the nation. He cannot resume his former role as if nothing untoward had happened. He had to acknowledge his own sin and culpability to both Yahweh and those he had abused, hurt and upset and humbly plead for forgiveness. He then had to wait until they had considered this new situation, absorbed the implications and then decided how to respond. That would not be easy for there were literally many thousands of people who had been damaged by David’s actions and each one surely had the same right David had, to take their own journey of grief toward their personal healing and recovery.

57. Only then can all parties journey toward reconciliation and restoration of their relationship.

58. This is difficult enough between individuals such as after marital unfaithfulness or a broken friendship but when a whole community is involved at varying levels of involvement and suffering it has to be dealt with in public with great wisdom and interpersonal trust.

59. However, all who are involved are not alone. Yahweh is a God of healing and restoration both communally and personally. Reconciliation is possible because Yahweh is involved. Yahweh wants his people to be reconciled.

60. It all comes back to the key biblical teaching of living by faith. David, his advisers and the tribal and communal leaders and even the people themselves did not have to work out what to do. That was Yahweh’s role and Psalm 3 provides an insight, a hint, about how this was achieved. See Psalm 15, notes 24-27 for a comment about this process.

61. Though Psalm 3 speaks into this situation it provides only a ‘snapshot’ of one particular aspect – David’s offer of an ‘olive branch’ to those who have been aggrieved by his behaviour. But that leads us to gain further insights into the narrative in which Psalm 3 is set.

62. David acknowledges that he was in trouble having seriously upset many citizens (strophe A) but he was now confident that he had been forgiven and restored – Yahweh had responded positively to his plea for mercy in Psalm 51 – and now, some 10-15 years later, after, I propose, Sheba’s failed rebellion, he sensed that he had been restored to Yahweh’s favour and was once again the nation’s rightful and Yahweh-ordained king (strophes C, X, X1, C1). His evidence for this was in the peaceful and restful sleep he enjoyed (strophe X1). He therefore felt he had the right to punish the rebels but confirmed that this would be measured and limited (strophe A1). All this was due to Yahweh’s work in his life. David expected the whole nation, the king’s faithful followers and those who had rebelled, could, and hopefully would, share in his experience of Yahweh’s blessing (Stanza 2).

63. I think the rebels would begin to be reassured by this. As King, David had the right, humanly speaking, to rule and insist on his way but David was not acting high-handedly, demanding his ‘rights’ and insisting on unquestioning obedience. He was conciliatory. As their king he asserted his authority and right to punish those who rebelled against him but stated this in figurative language so the broken and hurting people on both sides could be reconciled with each other and be reunited before Yahweh as Yahweh’s people. To achieve this, David renounced his right to punish the rebels and handed over this responsibility to Yahweh (strophes B1 and A1). He used humour and seeming irreverence to make this point thus implying that any punishment would not be severe and such were the possibilities in a ‘boxing match’ they might emerge unscathed. Unstated, but underlying the way this is expressed, is David’s awareness that he had experienced Yahweh’s mercy, so why not the rebels also?

64. This is entirely contrary to the way rulers normally acted (see for example, how Solomon and then Rehoboam treated the people in 1 Kings 12:1-16).

65. We need to bear in mind too, that we are all sinners. None of us have the right to sit in judgement on others. That is Yahweh’s prerogative:

It is mine to avenge; I will repay (Deuteronomy 32:35).

Do not repay anyone evil for evil. Be careful to do what is right in the eyes of everybody. If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone. Do not take revenge, my friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “It is mine to avenge; I will repay,” says Yahweh. On the contrary: “If your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink. In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head.”[3] Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good (Romans 12:17-21).

66. Yahweh’s mercy, his undeserved favour and forgiveness is a feature throughout OT such as in:

For Yahweh your God is a merciful God; he will not abandon or destroy you or forget the covenant with your forefathers, which he confirmed to them by oath (Deuteronomy 4:31).

But in your great mercy you did not put an end to them or abandon them, for you are a gracious and merciful God (Nehemiah 9:31).

They remembered that God was their Rock, that God Most High was their Redeemer. But then they would flatter him with their mouths, lying to him with their tongues; their hearts were not loyal to him, they were not faithful to his covenant. Yet he was merciful; he forgave their iniquities and did not destroy them. Time after time he restrained his anger and did not stir up his full wrath. He remembered that they were but flesh, a passing breeze that does not return (Psalm 78:35-39).

‘Return, faithless Israel,’ declares Yahweh, ‘I will frown on you no longer, for I am merciful,’ declares Yahweh, ‘I will not be angry forever (Jeremiah 3:12b).

The Lord (adonnay) our God is merciful and forgiving, even though we have rebelled against him (Daniel 9:9).

67. Yahweh’s heart is for reconciliation and recovery from the effects of sin and traumatic experiences. Punishment, rejection and banishment was not part of Yahweh’s plan or expectation for his people in the biblical record nor are they in our world.

68. Psalm 3 is a positive, encouraging psalm when a leader has sinned, treated his followers with disdain and abused them. Even in such awful situations Yahweh lives up to his name as the ‘Always I Am’ who is forgiveness and mercy embodied. The sense of this name is echoed by Jesus’ statement,

And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Counsellor to be with you forever – the Spirit of truth. The world cannot accept him, because it neither sees him nor knows him. But you know him, for he lives with you and will be in you. I will not leave you as orphans; I will come to you (John 14:16-18).

69. So David ends in the single strophe, stanza 2, by encouraging Yahweh’s people to live in the light of Yahweh’s presence for the benefit of his rescue and blessing.

70. Psalm 3 is set in the time when David had recovered his self-confidence, his awareness of Yahweh’s presence and guidance and his astuteness as a leader. There is a remarkable change in David’s attitude and behaviour from when he ran in fear from Absalom to when he resumed his role as Yahweh’s anointed King and wrote Psalm 3.

71. There is no apparent explanation for this dramatic change but there is an incident in the narrative of David’s response to Absalom’s rebellion that helps us understand how this could have happened. This is key to our appreciation of how he could come to believe that Yahweh had rehabilitated him into his favour so he could truly speak to the nation as the king Yahweh had chosen and appointed to rule but doing that in a humble and conciliatory manner. It is recorded in 2 Samuel 15:24-26.

72. As David fled from Jerusalem before Absalom and the rebel army arrived, quite independently it seems, Zadok the priest gathered the priests who were on duty in the Tabernacle and they carried the Ark, that represented, more than anything else, the glory of Yahweh’s presence, to go with David. The folk-belief in the role of the ark in imparting invincibility (1 Samuel 4:1-11) may not have died entirely so having the ark with him would likely be seen as a sign of Yahweh’s presence. Now, surely, that was David’s opportunity to turn the nation back to himself and leave Absalom and the remnant of his followers as isolated renegades! Surely, Yahweh had engineered this so his ‘favourite’ could be restored!

73. David might even have chosen to stay in Jerusalem for the ‘possession’ of the Ark and the support of Zadok and the priests would speak more clearly than anything that he was still Yahweh’s anointed King. But David rejected this offer! Well, he would have the trappings of such approval but was it truly Yahweh’s approval?

74. And if David stayed in Jerusalem, he knew there would still be fighting (2 Samuel 15:14) – and probably a siege – with the risk of damage to the city and Tabernacle and harm for residents. Perhaps, too, there might have been a fear that more of David’s apparent supporters would be tempted to change sides and join Absalom – and even become spies or saboteurs – just like the role David had in mind for Zadok’s sons and Hushai (2 Samuel 15:27-37).

75. David refused to allow Zadok to go with him! He insisted the Ark return to the city. That was personally foolish but David put his possible future role as King firmly in the hands of Yahweh. Furthermore, by taking any potential battle into the relatively remote eastern areas of the country, only the rebels and David’s army would be involved with much reduced risk of collateral damage to the cities, towns and the populace as a whole. This would also play to David’s strengths for he had seasoned soldiers at his command and with a few days notice he could perhaps pull in reinforcements from around the country ready to withstand what he would hope would be a ragtag band of untrained and ill-prepared rebels.

76. Warfare, though, is never straightforward so David rightly acknowledged that the outcome depended on Yahweh:

Then the king said to Zadok, “Take the ark of God back into the city. If I find favour in Yahweh’s eyes, he will bring me back and let me see it and his dwelling place again. But if he says, ‘I am not pleased with you,’ then I am ready; let him do to me whatever seems good to him” (2 Samuel 15:25-26).

77. This was the key moment when David put himself in Yahweh’s hands as if to say: ‘I do not deserve Yahweh’s mercy and favour but if Yahweh rescues me from Absalom, I will accept that Yahweh has forgiven me and is reappointing me to my role as his chosen king.’

78. R.T. Kendall says:

I believe this was David’s finest hour. He showed that he desired God’s will for him more than he wanted the kingship. His fear of God transcended any personal wish he may have had to be king. He was so broken over his moral failure, and grieving the most high God, that he did not want to short-circuit God’s plan and purpose. This is when David most demonstrated that he was a man after God’s own heart.[4]

[That last phrase refers to Yahweh’s recognition of David as he stepped out into public life as a teenager (1 Samuel 13:14)].

79. Yahweh did rescue David dramatically and quickly and I think that experience gave David the confidence to act.

80. For us, Psalm 3 relates especially to circumstances when a Christian leader’s sinful behaviour has damaged his standing with God’s people who look to the leader for leadership. The process of recovery and reconciliation takes time, and invariably, a long time. The fallen leader cannot claim any rights as a leader. Instead, they need to provide evidence of their personal restoration in their relationship with Yahweh. Only then can any expectation they have of being restored to leadership be considered and perhaps accepted.

81. The work toward reconciliation is not one-sided. Those who have been abused and hurt may well be resentful, angry and perhaps vindictive and are likely to have become focussed on their own hurts and not as fully on Jesus as he calls us to be. They too, need to experience healing of their own traumas and forgiveness of any sinful attitude or behaviour they have adopted for it is only as they find their own healing and restoration that they can be party to the community’s healing and restoration. See The Experience of Trauma Healing for more information about this process.

82. Psalm 3 goes to the heart of how best to cope when going through difficult experiences for it shows that Yahweh lives up to his name as the ‘Always I Am.’ We truly can trust Yahweh in adversity. This is not only a personal need and experience for it affects us communally so is also an aspect of the reconciliation that is needed when a community, whether a family, neighbourhood, church or nation, is torn apart by disturbances, fallings out or conflict. And even when that disturbance or conflict is associated with a leader who has gone astray Yahweh is still available to trust and guide and help everyone find both personal and communal healing and restoration if the leader is to be rehabilitated into their former role.

83. It would be interesting to know if there is any evidence in the subsequent history of the nation, during David’s lifetime at least, if the impact of the teaching and experiences recounted in Psalm 3 had any impact.

84. Did David make peace with those he traumatised? Was there a satisfactory reconciliation? Did David persist with his conciliatory tone or revert to his former self-centredness, which is illustrated in Psalm 21)? Psalm 3 ends with such questions unanswered.

85. This is not uncommon. For example, Psalm 66 is about a programme for teaching neighbouring peoples about Yahweh but there is no report of its progress, success or failure and no apparent reference to this campaign appears anywhere else in Scripture as far as I can discover. Similarly, Psalm 88 relates to someone in the depths of despair, depression and hopelessness and the only clue to its satisfactory resolution is that the psalm was written and preserved.

86. However, there may be some clues in subsequent events that there was, eventually, a successful reconciliation.

87. Warfare continued though David (who was now well into middle age) was not actively involved (2 Samuel 21:15-22). He seems to have occupied himself with organising his ‘civil service’ that included religious activities as well as national administration and military systems (1 Chronicles 23:2-27:34).

88. And then he oversaw the collection of an enormous wealth of materials and resources that would be needed for the Temple that he designed to replace the temporary, tented Tabernacle, for his son Solomon to build (I Chronicles 22: 2-19). Only then comes a strong suggestion that the disrupted nation had been reconciled with each other and with their king, as leaders and people worked together to fulfil Yahweh’s calling:

The people rejoiced at the willing response of their leaders, for they had given freely and wholeheartedly to Yahweh. David the king also rejoiced greatly (1 Chronicles 29:9).

89. That led into David’s powerful prayer of worship and a humble acknowledgment of Yahweh’s goodness and blessing to both himself and the nation (1 Chronicles 29:10-19) and was followed by communal worship and thanksgiving (1 Chronicles 29:20-24):

David praised Yahweh in the presence of the whole assembly, saying,

"Praise be to you, O Yahweh,

God of our father Israel,

from everlasting to everlasting.

Yours, O Yahweh, is the greatness and the power

and the glory and the majesty and the splendour,

for everything in heaven and earth is yours.

Yours, O Yahweh, is the kingdom;

you are exalted as head over all.

Wealth and honour come from you;

you are the ruler of all things.

In your hands are strength and power

to exalt and give strength to all.

Now, our God, we give you thanks,

and praise your glorious name.

“But who am I, and who are my people, that we should be able to give as generously as this? Everything comes from you, and we have given you only what comes from your hand. We are aliens and strangers in your sight, as were all our forefathers. Our days on earth are like a shadow, without hope. O Yahweh our God, as for all this abundance that we have provided for building you a temple for your Holy Name, it comes from your hand, and all of it belongs to you. I know, my God, that you test the heart and are pleased with integrity. All these things have I given willingly and with honest intent. And now I have seen with joy how willingly your people who are here have given to you. O Yahweh, God of our fathers Abraham, Isaac and Israel, keep this desire in the hearts of your people forever, and keep their hearts loyal to you. And give my son Solomon the wholehearted devotion to keep your commands, requirements and decrees and to do everything to build the palatial structure for which I have provided.”

Then David said to the whole assembly, “Praise Yahweh your God.” So they all praised Yahweh, the God of their fathers; they bowed low and fell prostrate before Yahweh and the king.

The next day they made sacrifices to Yahweh and presented burnt offerings to him: a thousand bulls, a thousand rams and a thousand male lambs, together with their drink offerings, and other sacrifices in abundance for all Israel. They ate and drank with great joy in the presence of Yahweh that day.

Then they acknowledged Solomon son of David as king a second time, anointing him before Yahweh to be ruler and Zadok to be priest. So Solomon sat on the throne of Yahweh as king in place of his father David. He prospered and all Israel obeyed him. All the officers and mighty men, as well as all of King David’s sons, pledged their submission to King Solomon (1 Chronicles 29:10-24).

To my mind this is significant evidence that the nation and King were reconciled and relations between them and with Yahweh had been restored. And this had taken even more years!

90. Notice that the priority in Psalm 3 is not the reconciliation between the affected parties though that is clearly needed. Instead, the focus is about everyone being reconciled with Yahweh as a prerequisite for interpersonal reconciliation.

91. I think that this emphasis relates to David’s understanding of what was at the heart of his sinful behaviour with Bathsheba and Uriah that had major repercussions for their children and family, the army officers who colluded with him in having Uriah killed and eventually the whole nation. Though all were hurt and damaged by David’s sin he said, ‘Against you [Yahweh], and you only, have I sinned’ (Psalm 51:4).

92. That, of course, is factually untrue but David is not ignoring, dismissing or belittling the harm he did but instead he focusses on the biggest issue of all – he had offended and let down Yahweh, his God and Master. He had put his own selfish interests ahead of Yahweh’s. The hurt and harm he had inflicted on others was collateral to the sin of all sins in failing to live up to Yahweh’s calling and expectation. [Note that Joseph expressed this same point when tempted by Potiphar’s wife (Genesis 39:9)].

93. This is different to the natural, human way of seeking reconciliation where fingers are pointed, bargaining occurs, apologies and restitution may be made and there are hesitant and cautious attempts to develop a new relationship. But can there ever be a return to a previous dominant/subservient relationship of king and citizen, master and servant or even church leader and church member?

94. The godly and biblical way of seeking reconciliation does not apportion blame, nor does it focus backwards to the events that occurred. Instead, there is an acknowledgement that we are all sinners and as we fall away from Yahweh we pull others down with us. The Bible focusses therefore on our personal relationship with Yahweh. If we get that right then other issues come into correct perspective. That is the message of Psalm 3. I see in the events recorded in 1 Chronicles 29 (notes 86-87) evidence for this.

95. Frequently in these ‘Psalm Insight’ studies I discover richer depths than expected but this time I have been absolutely flabbergasted at the way this study has developed. As an afterthought I included in note 3 that readers might find some of my comments somewhat far-fetched. I hope, though, at the end of this study, it is clear that these are not my inventions but rather a reflection of what the psalm says bearing in mind it is laid out in a poetic form that seems to be unique to the ancient Hebrew language and it is considered in the context of the culture and circumstances in which the psalm appears to be set. My prayer is that what I’ve discovered will be read with an open mind and a searching heart. I am, though, more than ready to receive corrections and alternative insights that come to others.

Endnotes

[1] The ‘your’ in ‘your people’ is used 135 times in OT with reference to an individual (2%), a leader, such as a king or prophet (20%), members of the nation (16%) and of Yahweh (62%).

[2] Mark Ward, ‘Capitalizing LORD‘ in By faith we understand, a blog published 18 October 2015 < https://byfaithweunderstand.com/2015/10/18/capitalizing-lord/> [accessed 8 November 2024] in which he quotes from Luther’s Preface to his (German) translation of the Old Testament: ‘Whoever reads this Bible should also know that I have been careful to write the name of God which the Jews call “Tetragrammaton” in capital letters thus, LORD [HERR].’ This text is available in Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 35: Word and Sacrament I, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 35 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), pp. 248–249.

[3] ‘Heap burning coals on his head’ does not sound like a pleasant experience so it is usually understood to be a form of punishment or perhaps was a cruel way to make the recipient feel guilty for needing such largesse. Not at all! It follows on from providing food and drink so the next step in caring for the destitute is to help them take back control of their lives. One way to achieve that was to provide them with the means of lighting a fire so they could prepare their own meals. This was done by taking embers (coals) from one fire, that were then carried on a clay plate on the head where it was safer and where the breeze would enliven the embers, to where a new fire was planned. If this is the correct interpretation, the translation of the phrase, ‘In doing this,’ needs to be reconsidered. See Randolph W. Tate, Biblical Interpretation: an Integrated Approach, (Grand Rapids, MI, 2008, Baker Academic), pp. 199-200. The biblical focus is on the destitution and not on their status as ‘enemies.’

[4] R. T. Kendall, Here’s what my ‘finest hour’ will look like… <https://www.premierchristianity.com/christian-living/rt-kendall-heres-what-my-finest-hour-will-look-like/18081.article > [accessed 9Sep2024] and see also R. T. Kendall, Their finest hour: 30 biblical figures who pleased God at great cost, (Nashville, TN., Thomas Nelson, 2024), pp. 111-117.

Written: 9 August 2022

Published: 16 November 2024

Edited: 14 September 2025